A look into social mirroring inside the global food supply chain and the marginalization of women

Written by Brent Downey, Founder of Urban Stalk

It is the year 2023 and to some, it may seem like the battle for equality has leapt forward from even just the beginning of the new millennium, and to a certain degree it has. A high-school aged woman today has a lot more social, political, economic, and financial freedom than her grandmother would have had at the same age. In just two generations, women have seen major improvements to their wellbeing and enhanced their status to become more equitable in comparison to their male counterparts. These achievements are celebrated and admired - future generations of women have more opportunity than ever before.

However, there is much work to be done to ensure women's health and wellbeing in both Canada and globally. Women are still the leading child raising identity in the average household. Food access and the disparities of food affect not only women, but the next generation of society. To perhaps most Canadians, something as simple as food impacts women's health and wellbeing from economic freedom, personal safety and security, safeguarding their children, and supporting the longevity and prosperity of tribes, communities, towns, and cities.

As we move forward with this discussion, it is critical for a few key terms to be defined to support the education of you, the reader. Below is a quick overview of these terms:

Food insecurity 🡪 Food insecurity refers to the inability to access a sufficient quantity or variety of food because of (usually) financial constraints but other constraints are possible such as remote location and is an established marker of material deprivation.

Food deserts 🡪 Food deserts are low-income tracts in which a substantial proportion of the population has low access to supermarkets, grocery stores, or other means of retail (food distribution).

Food swamps 🡪 Food swamps are environments saturated with unhealthy foods because of the larger numbers of corner stores, and fast-food outlets contributing to unbalanced and nutritional deficit communities.

What can be most evidently depicted from these definitions is that governments, NGOs, and policy makers attribute food insecurity as a function of income and socioeconomic status. There is an underlying merit to this attachment as food costs money and it is logical to pay for food just like any other consumer product. So therefore, the more money you have, the more food secure you become (in theory). However, what Canadians and global citizens must recognize is that the global food supply chain should be understood as a mirror reflection on societal behaviour and norms.

In most cultures and countries (Canada included), women have been placed in subject and inferiority to their male counterparts. If we stay, for a moment, only on numbers and financial equations that root definitions of food insecurity, we see that on average women take home $0.89 cents for every $1.00 that men make in the same employment category and role. On a global level, this is more starkly depicted where on average women make 24 percent less than men, face more hazardous working environments, and see twice as many unpaid working hours than men.

From these statistics it is no wonder that 388 million women and young girls are classified as food insecure as of 2023. The COVID-19 pandemic has also had an adverse effect on food access at the global level, making the estimate of food insecure women as much as 10% higher than reported figures.

Because women and young girls are viewed as second class citizens, inferior to men, and of easier replacement in the workforce when compared to men, their economic position has contributed to a lower buying power of food. Over decades of patriarchal social and political policy and norms, global food supply chains have been constructed to favour men and male dominated populations. Access to meaningful and equitable employment and economic status does play an extraordinary part in food security for women.

Additionally, the prevalence of food insecurity is that of racial community grouping. Canada has a staggering 4.4 million food insecure people as of 2021 , with 80 percent of this population being categorized into five major sub-groups: women, children, visible minorities, indigenous populations, and rural and northern communities. A study conducted by The Broadbent Institute (external link) highlights that African-Canadian households experience food insecurity at 3.56 times the national average, or 28.4 percent of the 4.4 million food insecure people in the nation. When looking south of the border to the United States, it is estimated that 53.6 million people, or 17.4 percent of the U.S. population lives in either food insecurity or food deserts (i.e., more than 10 miles from the nearest supermarket). As in Canada, food insecurity does not affect Americans equally - African-American families are twice as likely to be food insecure than white or Caucasian households.

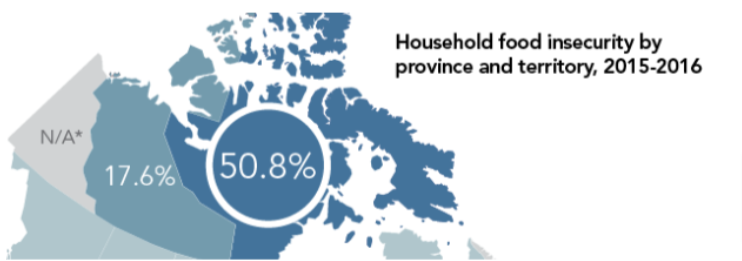

Figure 1.0 Food Insecurity Rate by Province in Canada as of 2020, Statistics Canada.

*2015-2016 as of the latest record in Canada’s Territories.

When narrowing our population focus from visible minority groups broadly to women in visible minority groups in Canada, Indigenous and African Canadian women are by the worse off with both groups facing almost 30 percent of women and young girls classified as food insecure as of 2022.

What we can take from all of this is that for women around the world, food access and inequality remain a consistent and prevalent societal issue. When we say societal, we don’t mean “just women” or “feminism”, or “bleeding hearts”. Through a study conducted by The American Academy of Pediatrics (external link) , there is evidence in both Canada and The United States that food insecure women are more likely to suffer from mental health disorders and their children are at higher risk for more severe mental health and even violent behavioural tendencies.

The study continues to highlight how food insecurity has a net positive association with crime rates and the prevalence of behavioural issues in the population. Continuing with social mirroring affects as well as an uneducated population (perhaps due to the latency effect of food insecurity), social stereotypes and xenophobic racism falsehoods can arise, creating further societal gaps and disparities that feed an already systematically (and racially) biased system. What if these communities had equal access to healthy foods, and their nutritional balance and environmental factors (quality of life) corrected behavioural tendencies and mental health disorders, therefore disproving racially motivated divides? Food security can most certainly have far reaching effects within ourselves, family, community, and society at large.

As a reader, we don’t want you to feel discouraged that the inequality engine is in too fast a motion to make a dent; this simply is not true. There are many positive changes happening in Canada (external link) and globally (external link) to ensure our social mirroring of the global food supply chain reverts to a mirror without cracks and chips. Women and female empowered organizations, governments, education systems, and the like are making active efforts to improve food security for women, by women, so the next generation of our world only knows food insecurity as a chapter in history books.

Sources:

Statistics Canada, 2020.

USDA Economic Research Service, 2022.

CDC – Preventing Chronic Disease, 2020.

Statistics Canada, 2022.

Oxfam Reports, 2023.

IBIS.

Broadbent Institute, 2020.

USDA Economic Research Service, 2022.

Social Policy Data Lab, 2021.