Science alumnus who chased a better future empowers next generation

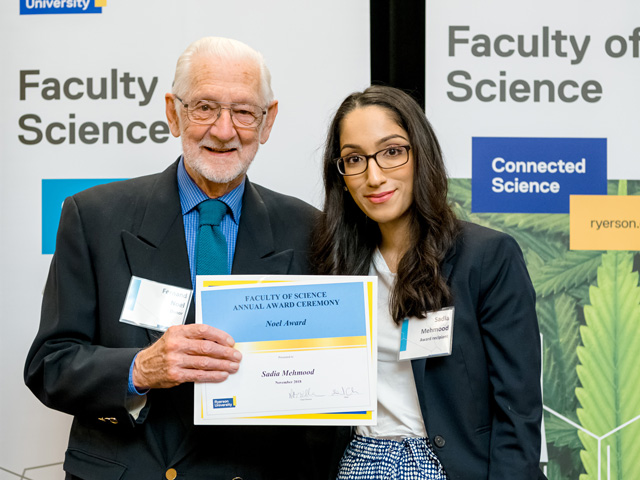

In 2018, Fern Noel generously endowed the Noel Award to the university, which has since honoured 11 Faculty of Science students, to date.

The journey toward deciding what you should do with your life sometimes starts with discovering what you shouldn’t do. For Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) alumnus Fernand (Fern) Noel, that journey began in the mines of Timmins, Ontario.

It was the summer of 1955. “Rock Around the Clock” sung by Bill Haley & His Comets topped the charts. A young Fern graduated from Grade 13 in high school and went to work underground.

“It was expected that I would support my mother and younger brother,” said Fern. “During August, I agreed to take a job for triple pay clearing the ore pass. It was 3,000 feet down, and I was suspended in a harness. After a few days, I decided I couldn’t do it anymore—this couldn’t be my future and I had to get out.”

He sought help from the only person he could think of—his high school guidance counselor. The school counselor helped Fern identify a program at what was then the Ryerson Institute of Technology (now TMU), fill out the application, and apply for a bursary.

“I had no money. The bursary would get me out and get me started,” recalled Fern. “Within three weeks, I was on my way. It was one of the hardest but best decisions I ever made. I had to take charge of my life.”

Fern Noel resting and reflecting at Dyers Bay after hiking and working on the Bruce trail.

Life before post-secondary education was “very hard.” Fern’s father was absent, and the family had little money. They lived in a three-room apartment—kitchen, pantry and living room—the latter being where all three of them slept.

“No one in my family ever had a higher education,” he said. “The expectation was you would go work in the mine or some manual job. In those days, working in the mine was dangerous, low status and poorly paid.”

However, going to school “allowed me into the world of science, which was my passion from a very young age,” said Fern. Even as a young teen, he set up a home lab in his family’s tiny apartment to study moulds, also known as mycology.

“Around 12 or 13 years old, I spotted an advertisement in a magazine to join an international science club for young people run by a doctor in South America,” said Fern. “He held a competition and first prize was a powerful microscope. I shared my experiments and won!”

Fern maintained his interest in chemistry and science throughout high school—even without support from home. So when he was accepted to study Chemical Technology in Toronto, he was on his way to finally living his passion—made that much more accessible thanks to a $150 graduation scholarship from his high school, a bursary from Ryerson, and support from his aunt.

Once in the city, Fern’s three flatmates paid his share of the rent, never asking for anything in return.

And at school, “I loved being surrounded by people interested in learning and science, and for the first time I was in an environment I wanted to be in and encouraged to be in,” he said.

“In my second year, I still had no money,” said Fern, “but my neighbour from Timmins, who understood my passion for education, loaned me the money. It was a really hard two years, but I survived through the generosity of all those people. I was lucky.” Fern graduated with his diploma in 1957.

After briefly working in the combustion engineering department at Stelco (now US Steel Canada), he moved to Sarnia when the Imperial Oil Research Department hired him as a research chemist. This was his dream job. Fern worked there for the rest of his successful, 33-year career.

“When I was hired by Imperial Oil Research, I was able to quickly make a real impact because (up until then) they only hired Grade 13 graduates as technicians with no training,” Fern said. “The boss of the department took me under his wing to help him solve some difficult problems. After I had been there for about a year, the research department shifted to hire more Ryerson graduates”— six to be exact. The year after that, they hired more.

Paying it forward

From the South American physician, to his flatmates, to TMU, the generosity of others enabled Fern to escape the hardships of his upbringing and shape his future.

“I was always interested in learning and education, helping and encouraging students. I really believed education was important and a route to better things. I had struggled and needed help and, through a lot of luck, I found it. Now, I could easily help financially. Supporting students at Ryerson was the natural choice,” Fern said.

Initially in 2015, he established the Noel Award in Science, a five-year award to recognize students who make a contribution to the university and who, like his younger self, also had financial need. In 2018, he endowed that award with a significant gift to the university. The award is now offered in perpetuity, providing over $4,000 each year to a student in the Faculty of Science.

In 2022, then-Medical Physics undergraduate student Neha Nasir received the Noel Award in Science. Before receiving the award, Nasir co-founded TMU’s Women in Physics committee, co-chaired the 57th Canadian Undergraduate Physics Conference in 2021, and was co-president of the Medical Physics course union at that time. She also volunteered at the Science Rendezvous, which turns Gould Street on campus into a science fair for elementary school kids.

“It was great to see my involvement within the faculty had actually made an impact on students and the community,” she said. “Thank you to Mr. Noel and his family. Financially, the award was genuinely helpful because it meant I could go a semester without working a part-time job and could focus on my studies, gaining research experience, and participating in extracurricular activities.” After undergrad, Nasir went on to pursue a MSc in CAMPEP Medical Physics.

Fern Noel met his wife Elizabeth at a singles dance in 1958.

A legacy that lives on

Before his death in February 2024 at age 89, Fern rarely missed an award’s ceremony and loved meeting recipients. “It is very gratifying to be able to lend my support,” he said at the five-year anniversary of the Noel Award in Science. At the last awards ceremony in February 2024, his grandchildren Jessica and Everett Johnston attended in his stead.

“Early in my first term as Dean in the Faculty of Science, I had the great pleasure to meet with Fern in one of the Kerr Hall labs that he frequented back in the day,” said David Cramb. “Fern was deeply engaged and passionate about helping students afford the great education he felt that TMU Science could give them. He particularly wanted to help under-represented students, such as those who are Indigenous. Fern's passion for education was infectious and it was an honour to know him.”

Two days before Fern died, he told his children, Diana and Paul, “What is important is how people remember me and what I have done—my legacy. That means I will live on.”

“Those words were powerful,” said Paul. “His work touched and impacted the lives of us all through everyday products that he improved or helped make safe through chemistry and science.”

Paul added that his father was very active in the Sarnia community, including with local nature programs in Ontario, helping to establish several hiking trails, including a section of the Bruce Train in the Bruce Peninsula; volunteering for 20 years with a local Adopt a Scientist program, which supports, motivates, and inspires school children “to be curious, to question”; and leading numerous camping expeditions to inspire people to learn about nature and how to be in the wilderness.

“He never wanted to just attend meetings or groups, but do something, to lead, to get results,” says Paul. “My father was restless in his pursuit of having an impact. Legacy is not just what you do but also in how you are remembered. That’s what he would want to share with others.”