Why we need substantive action in reconciliation

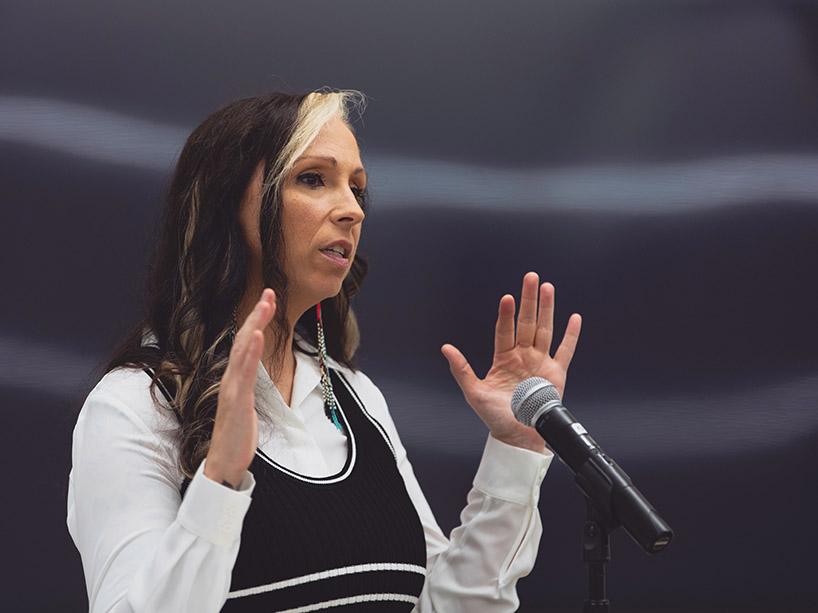

Pamela Palmater, Mi'kmaw lawyer, professor and chair in Indigenous Governance at TMU, opens Indigenous Education and Treaties Week with a powerful keynote address. Photo credit: Nadya Kwandibens.

Reconciliation is an ongoing, reciprocal relationship—one rooted in respect for mutual rights, says Pamela Palmater, a Mi'kmaw lawyer, professor and chair in Indigenous Governance in the Faculty of Arts at TMU.

“Reconciliation requires both symbolic and substantive action,” Palmater explained in her keynote talk opening the university's recent Indigenous Education and Treaties Week. “While symbolism, like changing political rhetoric and societal norms, is crucial for shifting how we perceive Indigenous Peoples, it must be coupled with concrete respect for rights—treaty rights, land rights, and inherent rights.”

Noting the complexities of reconciliation, Palmater urged both symbolic and substantive action to address the historical and ongoing injustices faced by Indigenous Peoples. The talk set the stage for a week of reflection, dialogue and learning about the importance of Indigenous treaties and the need for a renewed relationship with Indigenous communities.

Reconciliation requires more than symbolism

Palmater emphasized the critical distinction between symbolic acts and substantive change in the reconciliation process. While symbolic gestures, like the renaming of Toronto Metropolitan University, play an important role in acknowledging colonial histories, they must be paired with meaningful actions.

Pamela Palmater highlighted the need for reconciliation to move beyond symbolic acts toward meaningful actions. Photo credit: Nadya Kwandibens.

The renaming of TMU, Palmater noted, is an example of how an institution can demonstrate greater respect for Indigenous communities. However, such a gesture only becomes truly meaningful when accompanied by concrete action, like hiring more Indigenous staff and faculty, offering more Indigenous courses, and fostering a meaningful relationship with local First Nations and urban Indigenous Peoples. These efforts, she stressed, must include the consistent recognition of Indigenous Peoples' rights and a commitment to end the genocide of Indigenous peoples.

For Palmater, true reconciliation can only be achieved when there is full recognition and implementation of Indigenous rights in both policy and practice. This includes an unwavering commitment to respecting treaties and land rights, which, according to Palmater, are not mere legal obligations, but also support Indigenous self-determination. Treaties are not just about rights; they represent promises to protect one another, especially when we're under attack,” she said.

Treaties: a foundation for solidarity and mutual respect

Far from being relics of the past, treaties between First Nations and settler governments are living agreements that embody an ongoing commitment to mutual support and protection.

Palmater noted the importance of solidarity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups, drawing attention to the powerful alliances formed during the Idle No More and Black Lives Matter movements. These cross-cultural partnerships demonstrate that social justice is a shared cause and that solidarity is key to addressing the systemic issues that Indigenous Peoples face.

“One of the very first groups to come to us and march downtown [during Idle No More] was Black Lives Matter,” she reflected. “That formed a relationship, a new relationship that we didn’t necessarily have on the social justice front.”

For Palmater, this sense of community and solidarity is the very essence of what treaties represent, and now includes many others like Stop Asian Hate, anti-homelessness, and anti-poverty groups

"We are not in this alone," she said. "We need to think about that more. When you have backing, when you have soldiers with you, fighting this war is a lot easier." Treaties, then, are not just about securing rights for Indigenous Peoples; they are about creating a shared future based on respect, prosperity and protection for all communities.

The importance of Indigenous Education and Treaties Week

Initiatives like Indigenous Education and Treaties Week at TMU are critical for raising awareness and fostering deeper understanding of Indigenous issues. Through meaningful dialogue like Palmater’s keynote, students, faculty and staff are invited to engage with the history, complexity and ongoing significance of Indigenous rights and treaties. As Palmater stressed, understanding the true meaning of treaties is essential not only for building stronger relationships with Indigenous communities but also for ensuring that these relationships are grounded in respect and action.

Indigenous Education and Treaties Week at TMU highlights the importance of understanding and respecting Indigenous rights and treaties. Photo credit: Nadya Kwandibens.

"We have been treaty-making long before Europe even knew what a treaty was," Palmater said, stressing the importance of Indigenous governance systems that have existed for millennia. She called on the TMU community to reflect on the university's role in advancing this ongoing journey of reconciliation, both symbolically and substantively. For Palmater, reconciliation isn’t a final destination—it’s a continuous process that requires sustained commitment from everyone.