How does the Uncle Tom stereotype play out in the 21st century?

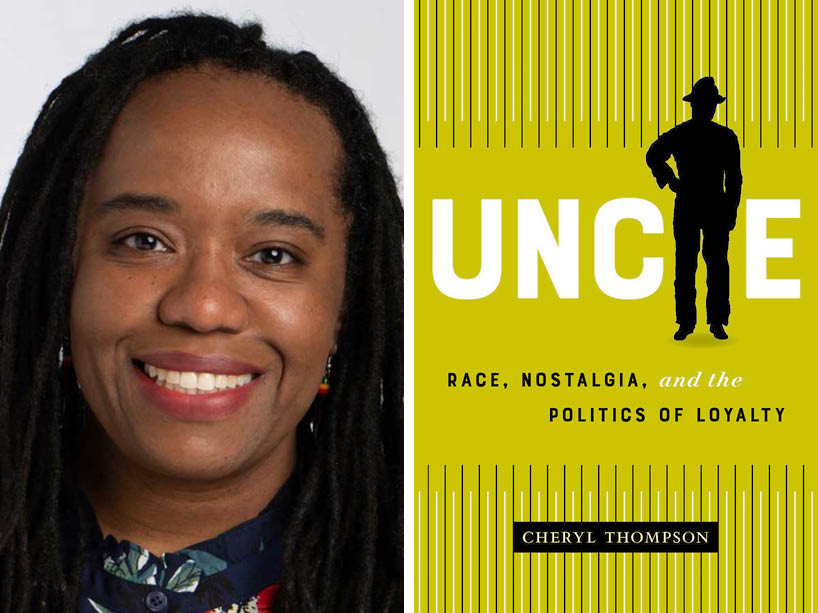

Professor Cheryl Thompson in the Creative School’s School of Performance unpacks the “Uncle Tom” trope in her new book, Uncle: Race, Nostalgia, and the Politics of Loyalty (external link) .

Professor Cheryl Thompson was completing her PhD at McGill University during a tumultuous decade. “It really started with the killing of Trayvon Martin (external link) – what followed was a lot of Black death, Black people who were killed because they didn’t take the command that was given to them.”

These deaths were embedded in her psyche. “I started to think about what it is about the police as an institution that approaches a car and thinks that the good Black person has to listen to everything they say, every request that's made. And look – we just saw it again in Memphis with the killing of Tyre Nichols (external link) .”

The answer, she says, led her to her latest book, Uncle: Race, Nostalgia, and the Politics of Loyalty (external link) , where she unpacks the origins, history and legacy of the Uncle Tom trope.

The origins and legacy of the term ‘Uncle Tom’

The term originates from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin, and the titular character, Uncle Tom. “In the novel, Uncle Tom is a character who is very loyal, and the story centres on his sojourn from two different plantations,” says Thompson. ‘He ends up at a particular plantation where he is treated brutally, and yet he's still loyal. He befriends the plantation owner’s daughter, Eva, and is treated as her peer, even though there's a huge age gap.”

This set up the stage for the sleeping car porter, says Thompson. “The sleeping car service started in the 1860s and they hired Black men to essentially perform the role of an Uncle Tom: a friendly, almost childlike Black man who takes orders, bows and always has a smile on his face.”

A sleeping car porter employeed by the Pullman Company at Union Station in Chicago, Illinois, circa 1943.

Through the early 20th century, Hollywood films reproduced this iconography uncritically. “Not just with the sleeping car porter but the bellhop, the shoeshine boy – all the servant roles that you see Black men playing. Anytime you would see a Black character on film, they were probably in a servant role for white people,” she says.

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s confronted this trope head on. “We saw the anti-Tom emerge, in Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X, the Black Panthers – all these militant Black men that no one had ever seen and white America didn't know existed,” says Thompson.

Today, we still have this legacy of the Uncle Tom and the anti-Tom dichotomy, and it gets reproduced in culture through film and even news media. “My book covers the ways in which you can see this: when the news media comments on how a Black man is so well-spoken,” says Thompson. “My book, along with other scholars, makes the argument that this is why Uncle Tom is seen as a sellout to the race, because it carries this legacy of anti-Black racism. You're more interested in serving than disrupting or actually thinking about your community and uplifting and working as a collective. That’s still playing out in the 21st century, even though it's a character from a novel from nearly 200 years ago.”

What Uncle Tom means for progress and Black politics

Thompson says that her research has led her to draw a through-line from Uncle Tom as a character, to the sleeping car porter, to the death of Black people because of police brutality. “If the sleeping car porter was seen taking a nap, or eating or conversing with their colleagues, they could be fired or fined,” she says. “That means the Black body always has to be ready to respond to a white demand. There was a part of me that was trying to understand why a Black ‘no’ keeps resulting in Black death. I study history, so I just felt like the answer was in history.”

The trope persists, says Thompson, because it’s never left the psyche of the western world. “The idea of the Black person who you like, who's really nice, who is there to just stay in their place – that notion has always been appealing to the dominant culture, because the opposite of that means disruption of institutions, means protests, means fighting back, means demanding change.

In Uncle, Thompson covers some major cultural figures who members of the Black community have maligned by calling Uncle Tom, including Jackie Robinson, Former President Barack Obama, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas and football player and actor O.J. Simpson, on which Thompson spends a great deal of time.

“At one point O.J. said,’I’m not Black, I’m O.J.,’ at a time when other Black athletes were speaking out about civil injustices and the Vietnam War, O.J. Simpson was happy to accept his position of prestige and say nothing more,” she says. “For all intents and purposes, he was an Uncle Tom because he thought he was there to serve white culture in any way. And that is the legacy of Uncle Tom, is it about you or is it about the community?”

Lessons from history

Thompson hopes Uncle encourages readers to respond to her call to action, which asks us to examine this dichotomy closer and see patterns emerging in our own lives. “Blackness in the western world as it has been articulated since our arrival in the 15th century has always been vested in this idea of us being two people: there’s the one type, and the other type, and not a lot of nuance in between.

“One of the issues of our time is a lack of consciousness. We have to fill ourselves with insight to see patterns around us. When people read my book, they will realize that there’s a Blackness that’s been created that’s outside of our reality. That’s a caricature of Blackness, and it’s outside of myself,” she says.

To pick up Thompson’s book, Uncle: Race, Nostalgia, and the Politics of Loyalty, visit the publisher’s website (external link) . Her book is also available at the TMU Library.

Related: