Giving life to Life

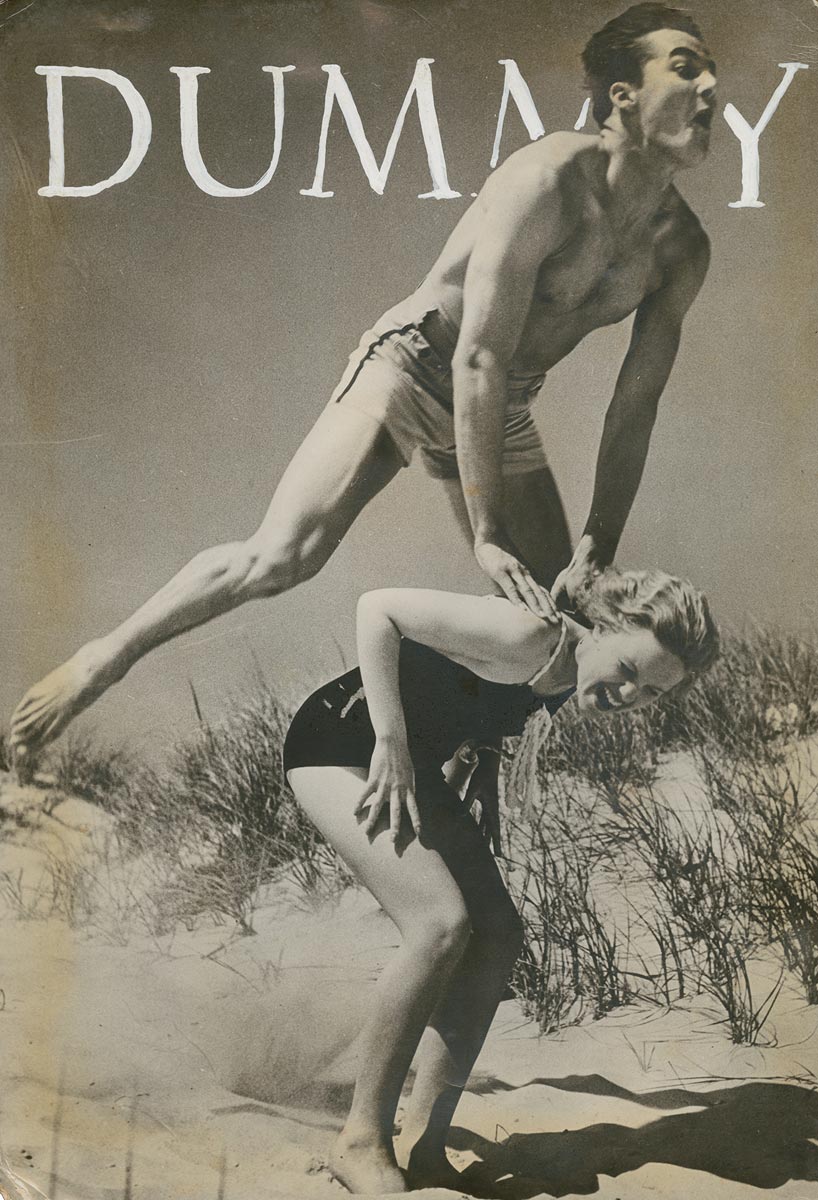

One of the dummy magazine’s cover photos shows a couple having fun on a beach during their holiday. Photo credit: Kurt Safranski, [Dummy magazine], ca. 1934, gelatin silver prints, lithographs, printed text, graphite and ink on bound paper. Ryerson Image Centre, Gift of Robert Lebeck Archive, 2019.

If you scan a news headline, or see a riveting image shared on social media, it is often the photograph that captures the power of the story and moves you to feel, to react.

The Ryerson Image Centre (RIC) has recently acquired what is considered to be “the Holy Grail” of a cultural artifact from photojournalism’s complicated history: dummy mock-ups that inspired the creation of Life – one of the most influential picture magazines in U.S. history and one of the major forces in propelling photojournalism’s sweeping influence in the media industry.

The creation of Life in 1936, in turn, led to the founding of the Black Star photo agency by aspiring publishing entrepreneurs and Jewish émigrés fleeing the Nazi regime: Kurt Safranski, Ernest Mayer and Kurt Kornfeld. The influential picture agency went on to provide countless memorable photos for the weekly news magazine, and countless other publications, bringing searing images of conflicts, world events and human-interest stories to readers everywhere.

“People can now study the origin of the most important picture weekly in the world, which is Life,” said Paul Roth, director of the RIC. “These [mock-ups] were sometimes spoken about, written about, but never seen in real life. And now, all of a sudden, they are here.”

The RIC was recently gifted two dummy magazines from the estate of Robert Lebeck, a prominent German photojournalist who possessed the most significant private collection of pictorial magazine in the world. The corporate archive for Time Inc., housed at the New-York Historical Society in New York City, has a third original dummy magazine.

“I had the good fortune of seeing Lebeck’s magazine collection a few years ago,” says Roth. “It filled — floor to ceiling, wall to wall — an entire apartment in Berlin. He had filled it with so many magazines, he had to live in another apartment elsewhere in the building.”

After Lebeck’s passing in 2014, his widow, Cordula Lebeck, was preparing her husband’s vast collection to be handed over to the German government when she came across the dummy mock-ups. After she had them appraised, she contacted Ryerson professor and RIC head of research Thierry Gervais, a leading expert on the history of photojournalism, to see if the RIC would like to house them for research purposes.

Roth says he hopes researchers will come to the RIC to study the mock-up magazines to uncover how they were created and the range of their influence. What is known is that the mock-ups were developed, in part, by Safranski, who emigrated to New York City in 1934 from his home in Germany. He, along with the co-founders of the agency and other associates, presented their mock-ups to Henry Luce, American media mogul and founder of Time and Fortune magazines.

Inspired by the mock-ups, Luce immediately pulled together his staff and used them to launch Life. The first issue rolled off the presses and into the homes of middle America in December 1936.

In its heyday, the magazine sold millions of copies in a week and was seen by tens of millions, fuelling the demand for more photojournalistic storytelling. The word, which once reigned as king, was slowly being pushed aside by the world’s appetite for compelling images.

According to Roth, the magazine was designed to reflect the lives of Americans in a weekly, capsulized format.

“If you’re in New York, and you don’t know what it’s like to be in a small farming community in Iowa, the idea was that you could know what that life looked like from this magazine.”

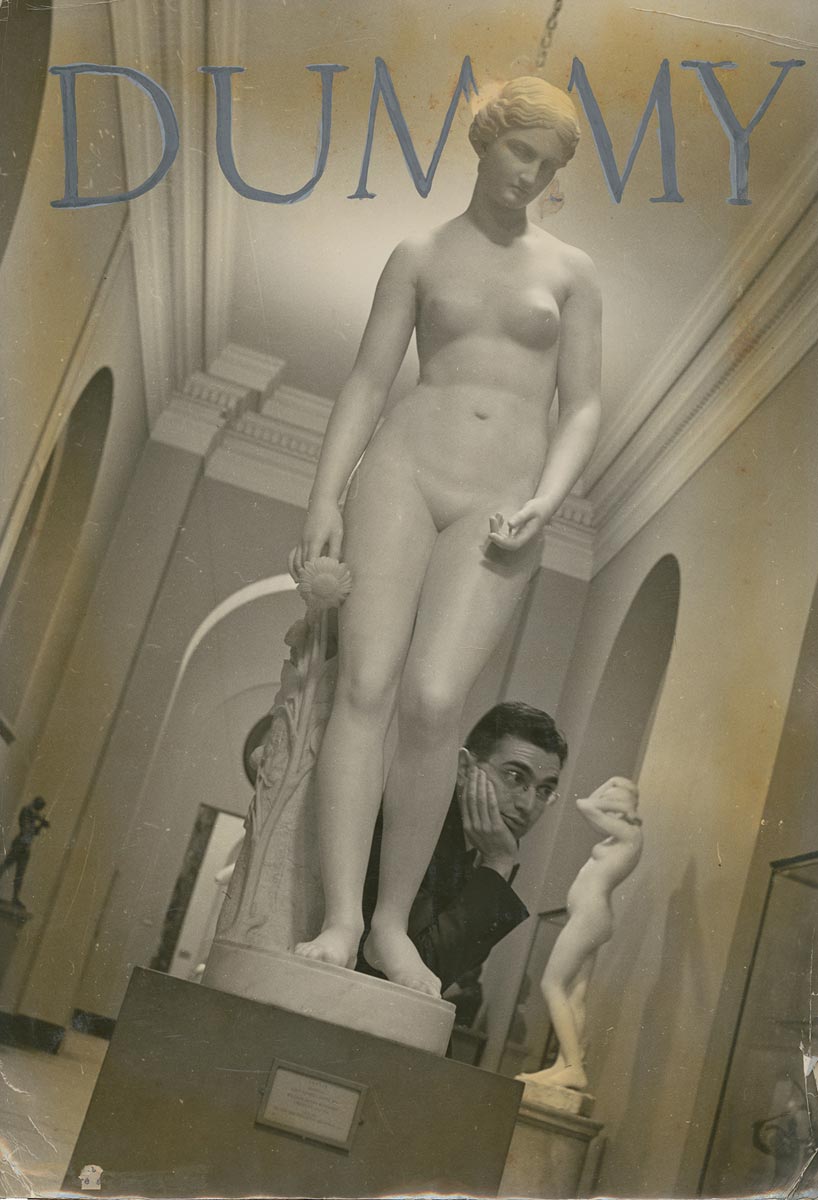

A second image of the mock-up cover portrays a nude statue in what looks to be a museum. Photo credit: Kurt Safranski, [Dummy magazine], ca. 1934, gelatin silver prints, lithographs, printed text, graphite and ink on bound paper. Ryerson Image Centre, Gift of Robert Lebeck Archive, 2019.

Inside the mock-ups

The dummy magazines created were a presentation of a collage of photos across page spreads, interspersed with short descriptions and text torn and pasted from other magazines. Roth notes that the mock-ups’ covers were designed to demonstrate the power of the magazine to move the masses.

“The whole point at that time was to convince a publisher such as Luce to produce a picture magazine which could be widely distributed, sell lots of ad space, and make lots of money,” he said.

The first cover shows people having fun while on holiday, a sign of the booming tourism industry at the time. The second cover demonstrated how sexuality could be introduced in a way that is more acceptable to the public. Roth points out that the photo on this cover partially covers the title, which is a way of animating the image so that it appears to “jump” out at the reader — a concept that was very progressive at the time in the publishing industry.

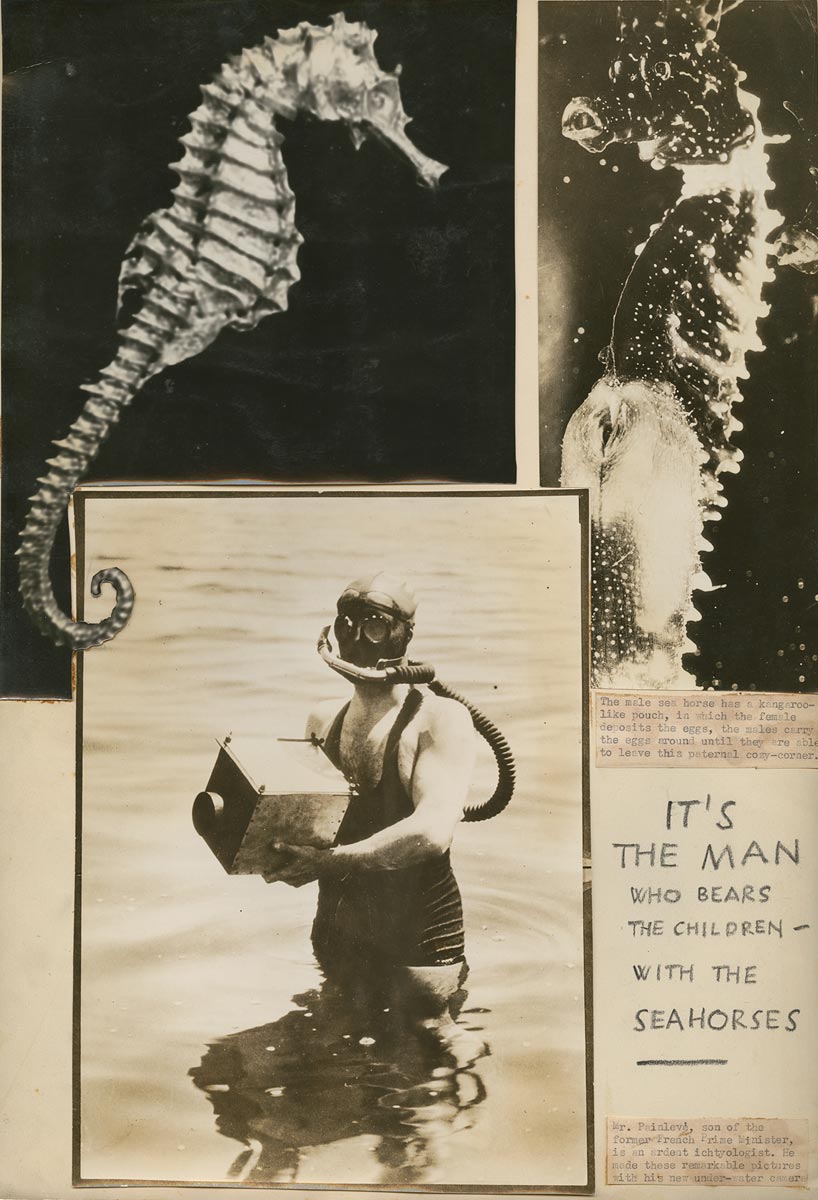

This digitized image from one of the dummy magazines demonstrates how the juxtaposition of photos with text can be used to tell a story. Photo credit: Ryerson Image Centre, Gift of Robert Lebeck Archive, 2019.

The photojournalists were also keen to convince Luce that a story could be told simply by the juxtaposition of pictures, says Roth.

“Photojournalism is often misunderstood as the making of a single image to sum up an event or personality. Just as often, photojournalism is a medium of storytelling, with multiple pictures and a narrative that emerges with sequencing and juxtaposition.”

Roth adds that text is also a key element of the dummies, used in interesting ways with different type sizes and placement on the page.

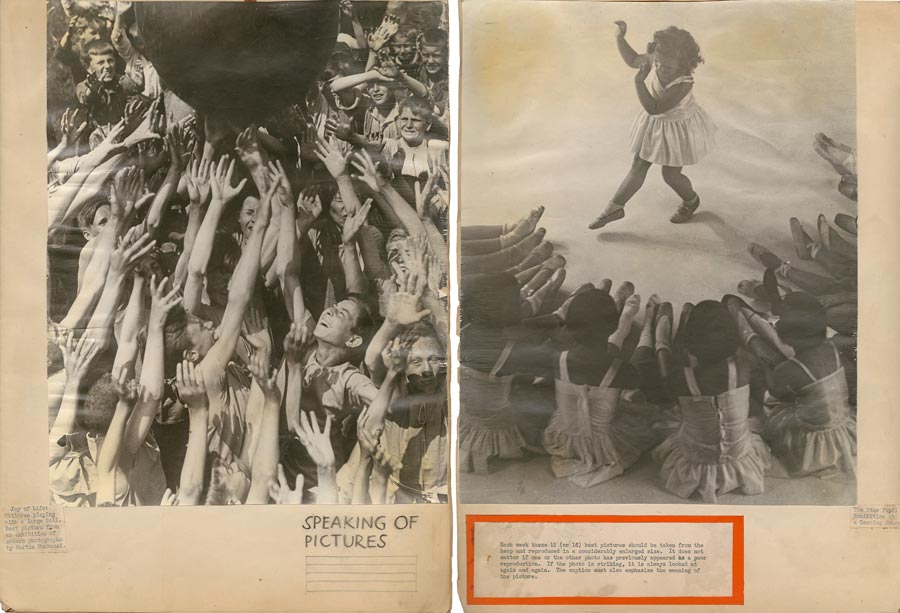

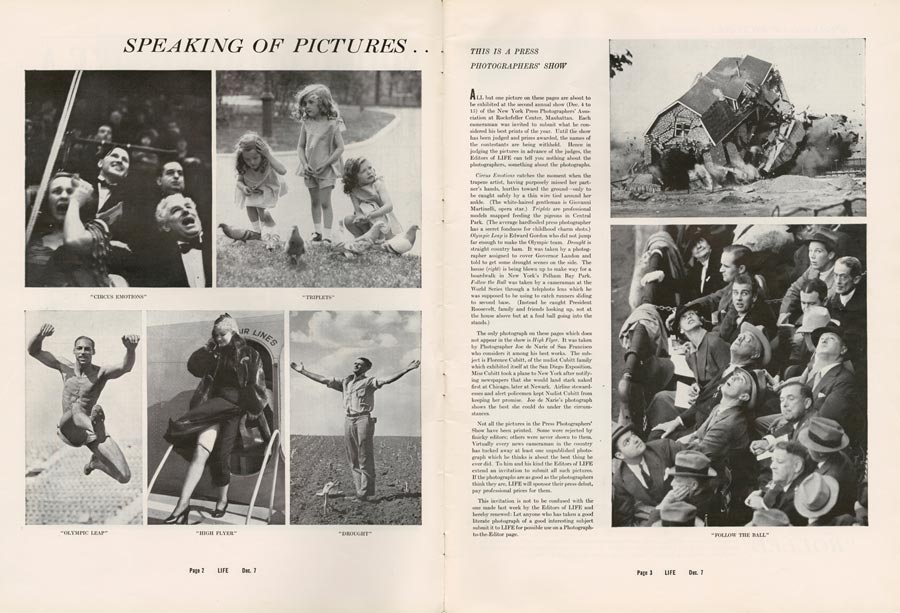

Kurt Safranski came up with the “Speaking of Pictures” concept, which he presented to Henry Luce. Photo credit: Ryerson Image Centre, Gift of Robert Lebeck Archive, 2019.

A clue that links the dummy mock-ups to the creation of Life was a section suggested by Black Star co-founder Kurt Safranski called “Speaking of Pictures.” This idea became a permanent fixture from the beginning of the magazine, presenting images to the readers that were surprising and wonderful, and at the same time, deeply humane.

Along with the prominent mock-ups, the centre also houses every unbound issue of Life magazine as well as the Black Star Collection of nearly 300,000 images. In fact, the RIC is planning an exhibit for the fall of 2020, to be titled Black Star: Stories from the Picture Press.

“We could not have imagined a scenario where these mock-ups would surface and be donated to our collection. It is extraordinary good fortune. It will be invaluable when people come to research them. Their scholarship will tell us what these dummies reveal about the great age of the picture magazine,” Roth said.

This “Speaking of Pictures” page spread ran in the third issue of Life magazine; the popular section remained a permanent feature throughout the magazine’s history. Photo credit: Life (December 7, 1936), pp. 2-3.