Award-winning researcher develops robotics for heart surgeries

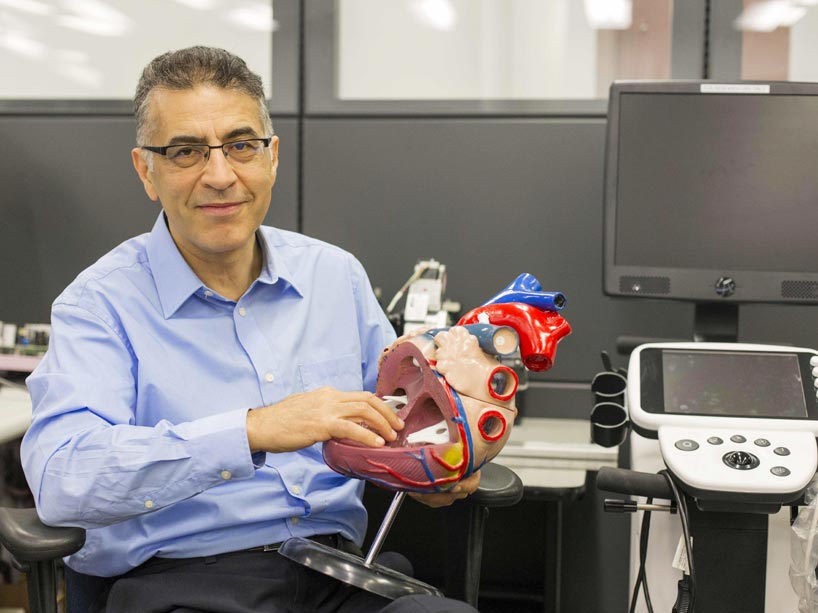

Photo: Farrokh Janabi-Sharifi, professor of mechanical and industrial engineering, is a leading expert in opto-mechatronics, the study of vision-based control systems for robots. Photo credit: Alia Youssef.

As a child, Farrokh Janabi-Sharifi was fascinated by robots. But it wasn't until he was a graduate student, talking with other robotics researchers, that he came to see the true power of the technology.

"Robots emulate our lives and help us to understand ourselves. They're more than machines; they are perceptive and communicative, and they're our future partners," says Janabi-Sharifi, a professor of mechanical and industrial engineering at Ryerson University.

A world-leading expert in opto-mechatronics, the study of vision-based control systems for robots, Janabi-Sharifi is the latest recipient of the Sarwan Sahota Ryerson Distinguished Scholar award. The honour is presented annually to faculty members who have made an outstanding contribution to knowledge or artistic creativity in their field.

Janabi-Sharifi has worked with many graduate students over the years and is a prolific researcher. He has applied for patent protection internationally for four inventions, has written dozens of publications, and during the last five years, his work has been cited more than 1,600 times.

He credits a confluence of events for putting him on his current research path. In the early 2000s, with his graduate studies behind him, he began exploring areas in which he could make a significant impact. At the same time, he was introduced to a network of cardiologists through his circle of friends.

The new connections would mark a turning point for Janabi-Sharifi. Through those interactions, he came to the conclusion many heart problems could be treated via robot-assisted, minimally invasive surgery. Specifically, he learned about atrial fibrillation (AFib), an irregular heartbeat caused by abnormal electrical signals in the upper chambers of the heart. Affecting more than three million people across Canada and the United States, the condition can lead to blood clots, stroke and heart failure.

There are a few ways to treat AFib, including a non-surgical option called catheter ablation. A thin, flexible tube is inserted in a large artery in the thigh and guided to the area of the heart where the problematic electrical activity originates.

The physician then destroys the malfunctioning tissue, using the catheter to deliver radiofrequency or laser energy, or a freezing treatment. From then on, the scarred tissue no longer sends out abnormal signals.

The problem is, humans have shaky hands. Also, the catheter is difficult to manoeuvre into place and doctors must rely upon grainy X-ray images when trying to see the targeted tissue. Therefore, many wrong spots are ablated before reaching the right position. Finally, the process exposes patients and staff to hazardous X-ray radiation for a lengthy amount of time.

Janabi-Sharifi wondered if robotics could, quite literally, lend a hand. He developed a robot that automates the ablation process, and according to animal studies conducted by his team of cardiologists and graduate students at St. Michael's Hospital, the machine performs the procedure with greater precision than humans.

He has also developed an approach that enables robots used in cardiac interventions to learn by observation. The robots watch how humans bend, flex and rotate and adapt those movements to their own structures, eliminating the need for any programming.

More recently, Janabi-Sharifi has also begun developing a soft-robot prototype that can replace a malfunctioning mitral valve in the heart. The procedure, which tightens a vein surrounding the valve, is considered minimally invasive, and unlike conventional heart surgery, would not require physicians to saw through the breastbone, open the chest and temporarily place a patient on a heart-lung machine.

"It's a revolutionary idea," says Janabi-Sharifi, "and the goal is to save lives."

Janabi-Sharifi's research has received support from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Ryerson University, the Ontario Centres of Excellence and Mitacs.