RSJ alum's book shows the beauty in aging and staying creative

Creativity isn’t just about turning your imagination into reality, it’s a way people communicate to the world. Author and RSJ grad Emily Urquhart chose storytelling as her form of creativity. Better yet, she’s turned her passion into a career.

It’s not surprising to learn that Urquhart has been around creatives since she was a child. Her father Tony, an established painter and her mother Jane, an acclaimed novelist, showed her the importance of being creative and choosing an art form you can turn into a career. The artists and writers who passed through her house growing up were instrumental to her growth.

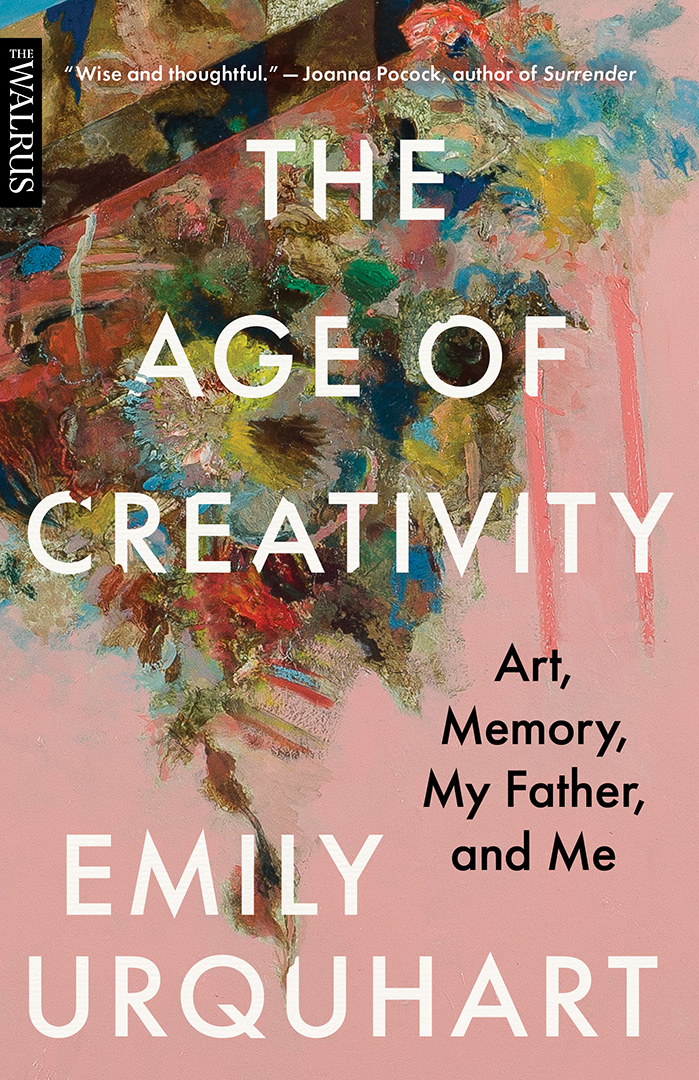

Her book "The Age of Creativity: Art, Memory, My Father, and Me (external link) " shows that personal creativity lives within humans forever, even as we age. It can come with its challenges as we get older, but it never goes away. Urquhart’s book illustrates the beautiful relationship she has with her dad, and her childhood memories of watching him create art. Urquhart interviews writers, actors and artists to learn about their creative processes. She began writing a different book at first, but the significance her father had in her life as an artist was crucial, so it ended up becoming a story about the two of them.

“I had an idea to write a book about creativity and aging. I wanted to show that people can still be creative and thrive with age; it’s not the conventual aging process we’re told about. My dad was supposed to be a small backdrop in the story, but that’s not what happened. I wanted to weave my dad in the story in a larger way,” says Urquhart.

Art has been Tony Urquhart’s main form of expression and also the subject he taught as a full professor at the University of Waterloo for almost three decades. He had the fortune of knowing what he wanted to do and what he loved at an early age.

“He’s always known he was an artist. He’s always been making art, and he knows that’s what he wants to do every day. He wakes up, eats breakfast and he goes to the studio and makes art,” says his daughter.

Although art is such a critical part of her life now, that wasn’t always the case. When Urquhart was growing up, having to constantly stand around and look at artwork was an annoyance. She had her first temper tantrum in the Sistine Chapel in Rome when she was two years old. She obviously didn’t have an appreciation for it then, but as she got older visual art became an essential part of her life — and it still is now, thanks to her dad. Art wasn’t only passed down to her. Her brother Aiden is a practising artist, and before his death 20 years ago, her brother Marsh focused on art as well.

Urquhart discovered going down memory lane and writing down her childhood memories was more of a challenge than she thought. Memories can change over time and people think they remember them exactly as they were. Childhood memories can be vivid and important, integral to development. She writes about how she remembers falling down the stairs as a kid into her father’s painting and how he remembers it differently. Tony has always been firm about how his daughter’s memories are her own and that she should tell them in the way she wanted to. “It’s interesting going back into that headspace again of being a child and looking at your surroundings and what that looked like. I tried not to put my adult views and understanding onto my child self,” says Urquhart.

The art studio of Tony Urquhart was always the centrepiece of his house. No matter where the Urquhart family lived, Tony had to have his studio. In earlier years when the family lived in a small town, the art studio was in the basement, but eventually the family moved to the countryside and when he was more established in his career and more financially stable, he built one in the backyard. Growing up, Urquhart felt the studio was a fun place for her to explore and watch her dad work. “When I was in kindergarten, I was confused about why other fathers didn’t have a studio and I felt bad for my friends. This was an example of how you see the world and how your life is constructed for you as a kid.”

When Urquhart was growing up, she would accompany her father on yearly art trips across Europe. Tony would go overseas to look at art and draw. Urquhart remembers his love for going to cemeteries and drawing tombstones. The cemetery was a form of communication for him and drawing there inspired him. Urquhart understood at an early age she had much to learn from her father and now recognizes those trips were valuable. Tony’s packing skills weren’t what you call practical, however. While the average person fills their suitcase with clothes, a toothbrush and toiletries, all Tony thought he should pack on trips were his art supplies. “His luggage was always so heavy that he would have to pay the extra fee at the airport. And then coming home he would have to pay double the price because he collected catalogues and more supplies while traveling,” says Urquhart.

Now at 86, Tony continues to create art, albeit not the same way. Since being diagnosed with dementia, it has been a constant battle for him to continue to make art. Dementia can stabilize over time, but it doesn’t get better. Art is such a focus for him and he still strives to create pieces. “During the summer I spent time with my parents, and my dad gave a watercolour demonstration to my two kids. It showed me he still had his memory and role as a teacher,” says Urquhart.

While growing up with her father, Urquhart found she had a good memory and eye for art. So, she decided to study art history at Queen's University, but found she had more of a passion for writing when she took a creative writing course. After completing the JRAD program at Ryerson, she went on to get her PhD in folklore.

“I love asking people questions and learning about who they are. Everyone has a unique story.” She went on to receive a National Magazine Award and now continues to teach creative non-fiction at Wilfrid Laurier University. It’s clear her background played a critical role in who she turned out to be, and how creativity played a role in her development as an adult. “My parents were a huge influence in my life. They made me see that choosing an art form you’re good at and believing you can make it into your career was fulfilling. It takes you where you need to be in life.”