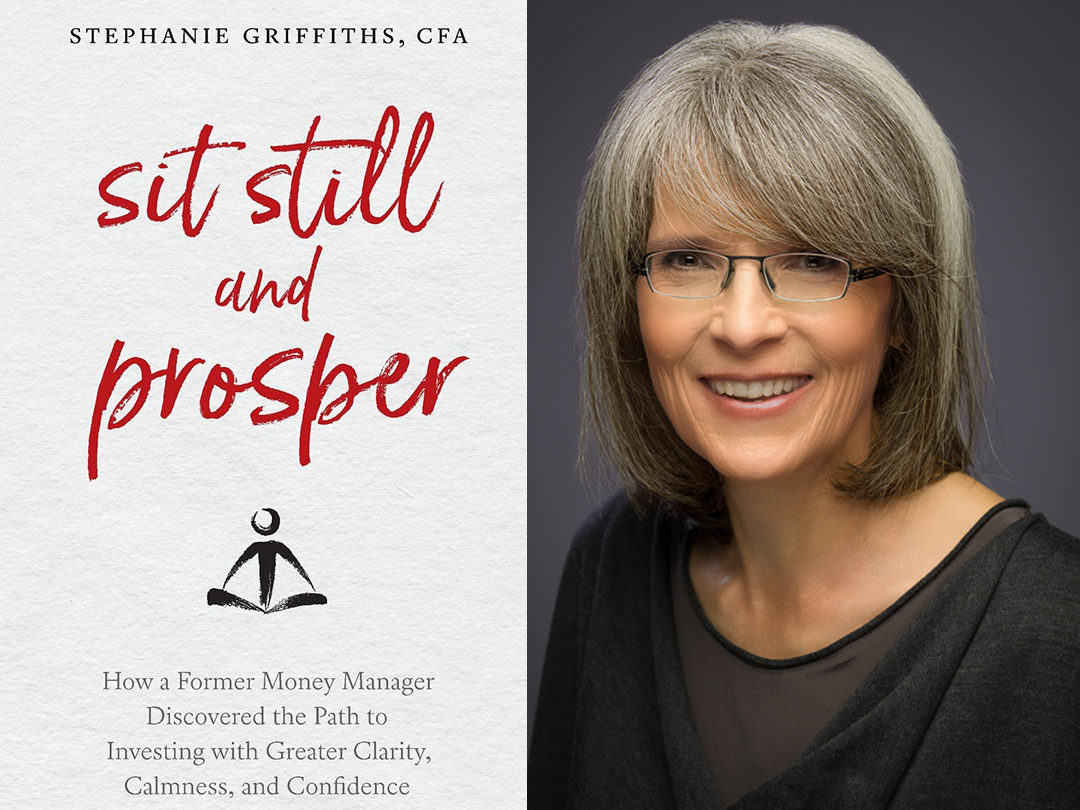

Interview with RSJ alum Stephanie Griffiths, author of "Sit Still and Prosper."

With 15 years of experience managing a mutual fund, Stephanie Griffiths (RSJ ’93) set out to answer the most common questions about investments in her debut book Sit Still and Prosper (external link) . After losing her job amid a hectic and successful career, Griffiths took a step back and applied teachings from her meditation practice to investing. With this new perspective, Griffiths offers simple, tangible and clear guidance into the complex – and at times intimidating – world of personal finances.

Griffiths answered some questions for RSJ about her book and writing process.

What inspired you to write this book?

When I left the industry in 2013 all my personal savings and my kids’ RESPs were invested in the fund I’d been managing. So, I suddenly found myself looking at the industry from a consumer’s perspective. And despite my financial background, the range of options was mindboggling. Around the same time, a friend of mine emailed me asking for investment advice and my reply went on and on and on and really wasn’t helpful at all. I was frustrated that I couldn’t provide a simpler answer. The book is really the story of my search for that simpler answer for my friend and, also for myself.

What do you think is the biggest misconception about personal finances?

I think many people have a very quantitative view of personal finance, that it’s all about numbers and budgeting, figuring out mathematically when you can afford to retire, or how much you need to save for your kids’ education. That’s part of it obviously, but one of the main themes of my book is that most of us measure wealth in other, more personal ways as well. A great example is the woman in the book who asked for investment advice from Sheryl Garrett, the US advisor who pioneered fee-for-service financial advice. When Sheryl discovered that the woman’s lifelong dream was to go to nursing school, she recommended spending her savings on that. Going back to school was a good investment based on the woman’s age, the local job market, and so forth, but also one that really paid off personally in ways traditional investments do not, ways that don’t show up on spreadsheets.

Why do you think people are so afraid to ask questions about investing and finances in general?

I think a lot of people don’t ask questions because they don’t want to appear ignorant or uninformed, so they’re reluctant to ask really basic questions about how a product works or what the worst possible outcome might be. When we buy a car or a TV, many of us are perfectly comfortable asking the salesperson whether he or she works on commission, but for most people, it seems impolite to ask the same question about financial products.

Another reason people often don’t ask questions is that many of us, especially after we’ve purchased an investment, really want to believe the marketing message, so we don’t dig too deep. This is one reason scams often persist as long as they do. For example, knowledgeable people questioned Bernie Madoff’s investment results for years before he got caught. Harry Markopolos tried to warn Madoff’s clients and the public through the media and the SEC, the US Securities and Exchange Commission, but no one would listen. So not only do we have to be willing to question our financial advisors, we need to be willing to question ourselves: is this decision based on research or wishful thinking?

It is obvious that there was a lot of research and work that went into writing this book, so were you at any point overwhelmed by all the information? How did you work through it?

That was the most humbling thing for me, trying to find a simple route through the complexity. It was always my goal for the book to be more entertaining than technical but I got very bogged down trying to address a lot of technical topics. The fee structure of mutual funds, for instance, is very difficult to write about in a non-boring way. They say it’s hard as a writer to “kill your darlings,” but once I changed my focus, I actually enjoyed deleting a lot of material I’d really struggled to try and breathe some life into. Basically I cut the book in half by reframing the question from “What’s best: mutual funds, ETFs, robo-advisors, etc.?” to “What’s the best way to make financial decisions that serve your own personal goals, whatever they might be?” I find the second question far more interesting, and I’m hopeful that other people will too.

Why do you think it's important for people to read this story?

Sit Still and Prosper (external link) addresses a lot of really common personal finance questions—Are robo-advisors safe investments? How do I know if my financial advisor is giving me good advice? How do I avoid running out of money in retirement? But it’s more about the decision-making process itself, rather than attempting to offer one-size-fits-all solutions. One of the main themes of the book is how truly personal and emotional investing actually is, even though it seems very scientific on the surface. For example, I can tell you a lot about how robo-advisors work and the potential pros and cons, but I can’t tell you if a robo-advisor is right for you. You may find the pluses less attractive and the downside more worrisome than I do, or vice versa. Either way, self-awareness is really crucial. In any decision, there are elements of the rational and the emotional, and it’s human nature to discount the influence of emotion, which is really what drives our decision-making a lot of the time.

What is the main message that you hope people take away from the book?

Investing is a lot more emotional than we often realize, so the more clarity and rational decision-making we can bring to it, the better. Actually, the title Sit Still and Prosper refers to work by Nobel Prize-winning economist Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein that describes human decision-making as a constant battle between our inner Mr. Spock, who makes purely rational decisions, and our inner Homer Simpson, who’s purely emotional and completely irrational. I think research has shown that we listen more closely to our inner Homer Simpsons more often than we want to admit.

What advice would you give to someone looking to learn more about meditation or finances?

Learning to meditate is a lot like starting an exercise program. You have to experiment a bit to figure out what works for you, and how to fit that into your everyday life. Then you need to stick with it for a while without expecting immediate results. You can learn almost any meditation technique online, but I think in-person instruction is more effective, because the instructor can help you with your posture, answer questions, and so forth. If you can find a group of people to sit with once a week, or attend a course that runs over a few weeks, that’s often helpful to stay motivated as you establish a regular practice.

On the financial side, I’m hopeful that Sit Still and Prosper (external link) is entertaining and helpful to anyone who reads it, but for financial advice, I’d encourage people to seek an independent financial advisor who can tailor his or her advice to your specific situation.

What was your process like completing the book?

After I left the investment industry in 2013, I wrote some essays on investing for my website. I submitted one of these as a writing sample with my application to the University of King’s College MFA program, a program designed to support aspiring authors of creative nonfiction books. The instructors at King’s are all talented nonfiction writers, so I had expert help through the research and writing process. Having regular deadlines really kept me on track, and I also learned about practical matters like book proposals, research plans, and interviewing. I finished my first complete draft of the manuscript after graduating in April 2016, but I wasn’t really happy with it. The manuscript was way too long and technical.

After shelving the project for almost a year, I did a massive rewrite, cutting out huge chunks of text and expanding some of the topics I’d found most interesting: meditation, diversity, decision-making, and socially responsible investing. Start to finish, the book took around four years.

What was one of the most surprising things you learned while writing the book?

Through my research, I met some incredibly inspiring people, pioneers of innovations I believe are really positive for consumers. Jon Stein, inventor of the robo-advisor, for instance, named his company “Betterment” before he even figured out what they were going to do; he just wanted to offer a better solution for investors. He and many of the other people profiled in the book walked away from successful careers and took significant pay cuts to work on projects they felt were about more than just money, which really inspired me.

I was surprised and extremely grateful for how generous these people were with their time. (Most of my sources were Americans, because with the exception of exchange-traded funds, the financial innovations the book talks about were made in the USA.) Almost everyone I asked for an interview consented and shared a lot of time and wisdom with me, an unknown writer from Canada.