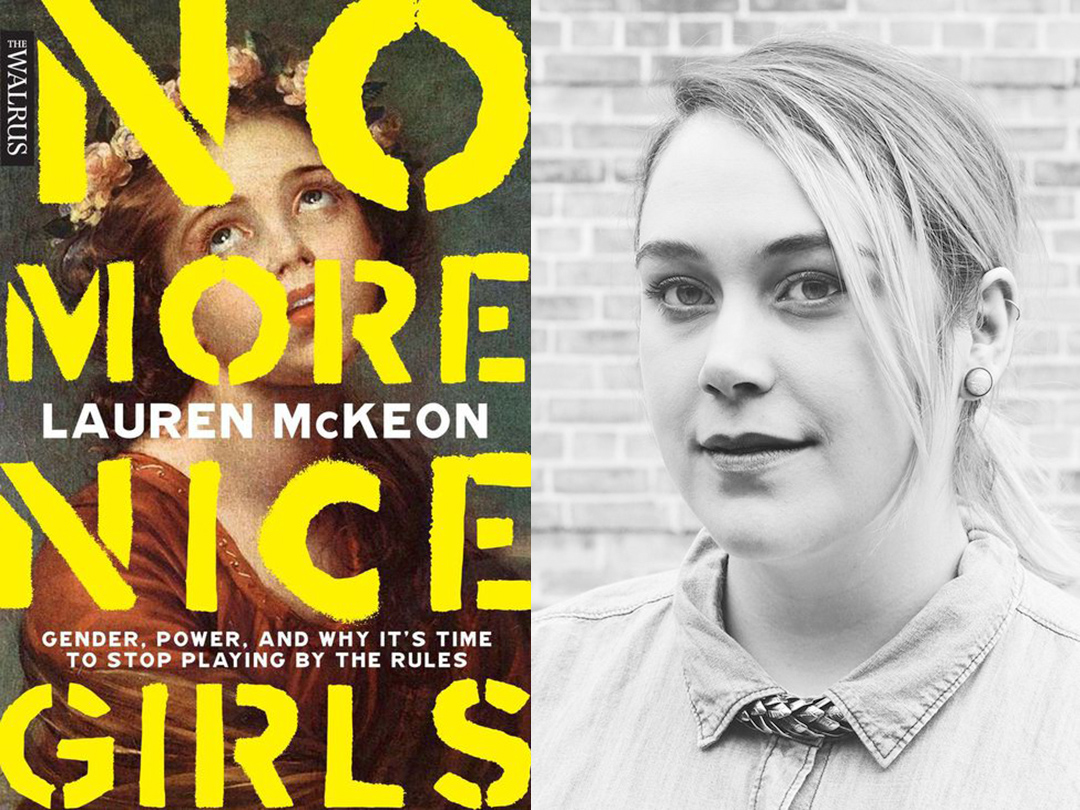

Interview with RSJ alum Lauren McKeon, author of “No More Nice Girls.”

Interview with RSJ alum Lauren McKeon, author of “No More Nice Girls.”

In No More Nice Girls (external link) , Lauren McKeon (RSJ ’07) explored the ways institutions are designed to keep women and other marginalized genders at a disadvantage and revealed why diversifying those institutions are not enough—the models of power have to be changed not replicated. McKeon talked to people in a variety of sectors about how they are changing the rules instead of playing a rigged game.

McKeon is deputy editor of Reader’s Digest Canada. Before joining Reader’s Digest, she spent time as digital editor at The Walrus, editor of This Magazine and as a freelance journalist.

What inspired you to write this book?

My first book, F-Bomb (external link) , ended on a scene from the Women’s March on Washington—this incredible moment of resurgent feminism. People were hopeful. People were angry. And I started to think about what came next. What would we do with these powerful feelings? What kind of world would we want to create? And what would it look like if we reimagined our systems of power? I wanted to talk to the many, many people who were already doing just that.

One of the dominant themes in the book is of the Girl Boss and the idea that breaking the glass ceiling doesn’t lead to more gender equality. How does that focus stymie making real change?

To be clear, I don’t want to advocate against more diversity at the top. We certainly should strive for more representation in traditional leadership. From business to government, we need to see more gender diversity and certainly more racial diversity. We need to see so much change. The problem is when we start thinking that’s all we need. Research has repeatedly shown that having a woman CEO, for example, doesn’t automatically generate a less sexist company—that diversity needs to trickle down to middle management, to employees, etc. It’s only then that we start to see true change, and the support for such change. Such change can’t, and shouldn’t, rest on one person; we need to change the system together.

Your book talks about how even through the modern feminist movement, our societal ideas of power and success have remained the same, which reinforces the existing power structures. Can you give an example of that and talk about how it’s harmful?

We often see this in our visions of what makes a good leader—and the contradictory, impossible standards to which we hold women leaders. We want women to be pleasant, but firm; attractive, but not sexual; warm, but not over-emotional; dedicated, but not ambitious; mothers, but not motherly; and the list just goes on. As part of this, we also tend to undervalue leadership styles and qualities we traditionally classify as feminine: collaboration, vulnerability, empathy, kindness, etc. I think many women know what it is to be caught in this trap. Luckily, if there’s one silver lining to the pandemic is that we’ve seen women leaders—and their unique leadership approaches—excel during this time. And, I think it’s making a lot of people appreciate there is not only one version of leadership or success.

What does a movement or effort that creates a new model of power look like?

We’ve seen many throughout history. Recently, we saw the #MeToo movement topple many existing power structures, and force people to pay attention to stories and experiences they may not have otherwise. In fact, we know that many of these stories had been ignored and buried for decades. Questioning power makes people uncomfortable. Case in point: the Black Lives Matter movement, which is sparking necessary, urgent change. The most recent call to defund the police—one of the clearest examples of a power structure rooted in racism, colonialism, classism, and sexism—has led to clear action in many places around the world. And the action of defunding the police itself is, I think, an essential step in helping us all to reimagine what models of power should look like.

What advice would you give to young people pushing for a more equitable future?

Honestly, I think young people are doing such creative, important work on this front already. They are protesting, they are taking to social media, they are speaking out, and they are meeting themselves to discuss important issues—taking action on everything from racism to the climate crisis. If anything, I’d tell them to keep going. And, I’d tell the rest of us to pay attention, to learn, and to support them.

What was the most surprising thing you learned while writing the book?

I learned a lot while researching and writing this book, but I wouldn’t say I was too surprised to discover we have a long way to go—or that so many people are working together to help us get there. I will say, though, that I was constantly inspired by the people I interviewed, who are all doing amazing things to reimagine power, success, and leadership. That work is rewarding and it is hard, and I truly appreciate them sharing it with me.

What was the most challenging aspect of writing the book?

Stopping! There are so many people doing such good work. And there is so much work to be done. I know many people will be writing about power, and the systems and beliefs that entrench our toxic visions of it, for years to come. I couldn’t cover everything and I’m so looking forward to seeing other voices weigh in and put forth new ideas and arguments.

What has the reaction from readers been like? Has the response been gendered?

Inevitably, yes, I have received messages from people who believe I’m what’s “wrong” with women, and that we’ll never achieve equality so long as scary feminists like me are around to discuss how far we still have to go. I’ve received more messages from people who told me the book has made them think, and to question things—and that’s all I really want. You don’t have to agree with me. So many people don’t! But I think we can agree that if our systems are leaving behind so many people, they aren’t working. We all deserve equity.

What advice would you give to people who are interested in writing non-fiction books and particularly pursuing feminist topics?

Writing a book is a long process, so if you are interested in non-fiction definitely pick something that is near and dear to you—a topic that you want to spend years on, something that is important to you. Find something that you want to say. That you have to say. And then get ready to do your research. I think this goes for any topic, and maybe especially feminism. A lot of people might not want to hear what you want to say. We have to find the courage to say it anyway.