Building a legacy of hope: new concept in trauma-informed care

Photo by Andre Hunter (external link) on Unsplash (external link) .

“...I watched my friend got shot in the stomach when I was in 7th grade. He was playing in the park when some guys open fire on a crowd of people. He died on the spot. For a long time, I didn’t leave the apartment, except for school.... I would have been a different person I think, maybe gone to university... I wish I could meet the person I would have become without the pain and trauma of that moment...”

— Research participant

For the majority of people in Canada, shootings unfold inside the safety zones of TV shows, news reports, movies and video games — watch or play, then walk away.

But in Toronto’s most disadvantaged neighbourhoods, gun violence happens in real time, close to home — actual human victims, authentic lead bullets — repeated tragedies with no “on/off” button.

With every new shooting — whether victim, bystander, friend, family member or resident — the entire community reels from yet another aftershock. Black youth, in particular, have disproportionate experiences with gun homicide loss. Prior research already bears this out.

Far less investigated is how these intersect with social and racial factors to increase risk and create a crisis of trauma for young survivors.

On the ground, long-time community advocate Gary Newman can nonetheless testify to the heartbreaking, life-altering impacts on Black youth in Toronto. But he’s also witnessed amazing journeys out of and beyond trauma — where youth have transformed their lives, used their trauma to help others and even become mentors themselves.

“In media reports, you hear ‘arrests’, ‘parole’, ‘probation’, etc. But on the flip side of that — if you target change differently for these young folks and invest in them — the outcomes can be so positive you’d never even know their history.”

— Community consultant Gary Newman

How can society shift the narrative that these youth “did it to themselves” and, instead, create more such positive outcomes? The key is a new understanding of how repeated, complex re-traumatization impacts youth over time.

Most recently, Newman teamed up with TMU nursing professor and expert on gun violence and survivorship, Annette Bailey. Together with co-authors in research and community practice, they presented a concept that sheds new light on the intersections of trauma and compounding factors on Black male gun violence survivors. The study, “Deconstructing the Trauma-Altered Identity of Black Men” (external link, opens in new window) , was published in the Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma.

Dominant themes in complex re-traumatization

A single traumatic event of any kind can wreak prolonged, disabling psychological burden on its survivor. But for the young Black males, trauma developed not only from recurrent gun violence, but compounding factors of living in marginalized environments.

“Trauma is something that lives under your skin; it never really goes away — particularly for these youth who also struggle with poverty, racism, difficulties navigating the school system, and lack of male role models and mental health support,” says Bailey. “They live in chaos every day and can’t make sense of why they're in this space. Our research looked at what all of these activated traumas do to a young person’s system — their mindset, their growth, aspirations and trajectory.”

Newman adds: “In the news, gun violence is labeled ‘senseless acts of violence’. But many times, it’s only ‘senseless’ until you know the full story. We need to dig deeper to find out what else is going on underneath.”

“These youth are often treated like they’re invisible. But when we speak to them with kindness in a space that makes them feel safe, seen and heard, they'll tell you things that the world needs to know.”

— Dr. Annette Bailey

During the research study, the youth shared many heartrending expressions about the psychological impact of their trauma, such as:

“You can’t be better in a neighbourhood like this. If I grew up in Vaughan, that nice neighbourhood in Wonderland, I would be a completely different person. When you move from the neighbourhood, you have a different perspective.”

“Hear this, the true definition of hell is when the person you are not supposed to become is the person you are, due to racism and trauma.”

“A lot of Black men are disconnected from who they are. They search for themselves in gang life and through an identity as someone else, someone to be feared. At the root of that is trauma, social struggles, fear.”

Recurrent themes emerged from the data, including feelings of entrapment by systemic oppression, an eroded sense of identity, and shifted conceptions of masculinity — a three-pronged concept which the researchers named the trauma-altered identity (TAI).

Behind the cage: Psychological entrapment

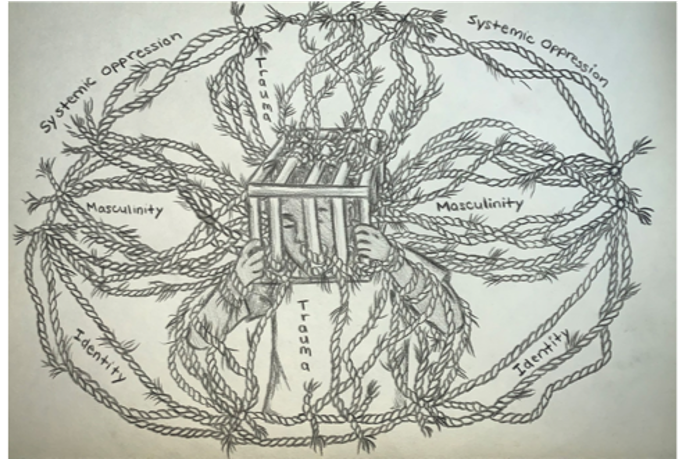

Artist representation of the trauma-altered identity, drawn by Megan Nguyen, co-author and arts-based researcher.

Trauma compounded by aggravating factors is complex. The researchers needed a simpler way to represent it. They found it through artwork by co-author and arts-based researcher Megan Nguyen, created specifically for the journal article publication.

“Folks aren’t going to tap into this with just new knowledge. We need ‘5+1 senses’ to make changes,” says Newman. “Art has no rules. You can express all your hurt in it. People need that.”

In the metaphorical piece, a youth’s mind is entrapped by a psychological cage. Thick, braided ropes tangle their experiences to create a trauma-altered identity (TAI). Inside the TAI cage, the victim has difficulty seeing different perspectives.

But most importantly, the ropes are fraying, symbolizing the hope, possibility — and very real occurrence — of dismantling the cage, as experienced by some of the research participants.

Learning to dream again

The trauma-altered identity (TAI) could be at the root of widespread psychosocial instability among Black youth. Acknowledging and addressing this underlying trauma is an important first step in freeing youth from its imprisoning effects.

“With the continuous, heartbreaking trauma that Black youth encounter, we can't expect their trauma trajectory — or their treatment strategies — to fit a universal definition,” says Bailey. “We have to understand youth based on their experiences and then modify practices to meet their needs. It’s about resetting how they view the world and their place in it, and helping them start dreaming again about the possibilities.”

“...now that I am in college my mindset is changing. I still struggle with the death, but I have a better sense of society now. Back then, the more of my friends killed by guns, the more I became numb and hard. I had my gun because I wasn’t going down like that. But [name of youth mentor] helped me see that I can be proud and Black. I am still a man without the gun...”

— Research participant

One of the most powerful strategies recommended in the study is culturally sensitive mentorship. Newman can attest to its effectiveness.

As an example, he points out the ‘peak times’ when trauma survivors most often reach out to him: not during the typical 9-5 service hours, but between 2am-5am while struggling with nightmares, sleepless bouts and self-medicating.

In one case, he devised custom tactics, such as pre-scheduling a string of daily 3am email messages to encourage one Black youth who had lost his brother to gun violence. After 10 years of mentorship and support, the young man finally accepted a referral for grief counseling. Seeing this, his younger brother also began expressing interest in getting help.

The study also made numerous other recommendations in community programming, trauma-informed care, and broader discussions on policy and social justice reforms. While the road to widespread systemic change may not be swift, Bailey shares the vision that keeps her staying the course:

“Hope is at the core of what we do. We often think of legacies as something one leaves behind, but they first need to be built. Investing in young people — no matter where they’re at, no matter how far they’ve gone — brings dividends and builds a legacy of hope.” - Dr. Annette Bailey