Working toward gender balance in computer science

One of Ryerson’s explicit goals is to substantially increase the number of students from equity groups in programs and departments where they are under-represented compared to the community. When it comes to gender balance, Computer Science is one such department. Department chair Dr. Dave Mason is committed to correcting that imbalance in both the student body and the faculty when teaching positions become available.

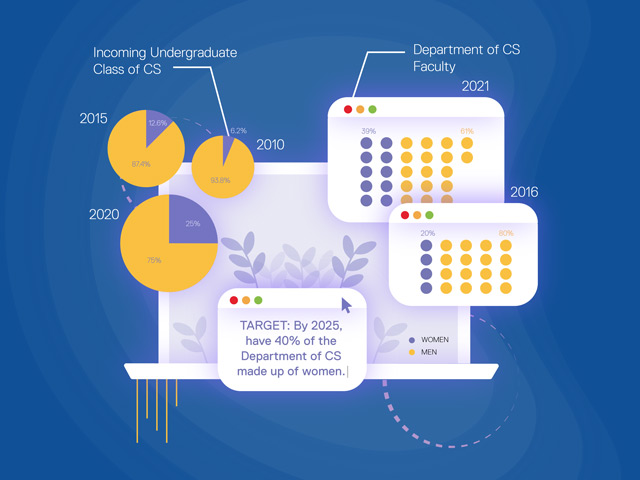

“Last year, 25 per cent of the incoming undergraduate class were women,” says Mason. “This is up significantly from 2010, when it was just over six per cent. Since the mid-80s, there has been a downward trend across North America of women entering computer science programs. The numbers are coming back up, but slowly. We’re working to attract more female high school students into our programs.”

It is possible that the dramatic upswing in online gaming over the past few decades has played a role in discouraging young women from pursuing computer science. There is some association between a stereotypical “boys in the basement” gaming culture and computer coding. Whatever the case, Mason says that getting female students through the door in the first place has been a challenge, as how young women experience the subject in high school and in popular culture has an impact on their post-secondary choices.

One solution: offer a new minor in computer science to Ryerson students outside the department as a way to gain basic knowledge of the field and, possibly, switch into the degree program if interested. The minor does not required any high school prerequisites, which is an asset for female students who may not have felt welcome in their high school coding courses or clubs.

But Mason adds, “We want women in the core program as well, and we’re continuing to work to attract them to coding camps and clubs and to change the stereotype of the ‘typical’ coder. Before the pandemic, we set a target of having 40 per cent of our undergraduate class by 2024 be women. We’re still working toward that, though the current upheaval makes change more difficult.”

The department is also working toward gender balance in faculty makeup. In 2017, there were 16 male faculty and four female faculty. Today, those figures are 17 and 10, respectively, an increase from 20 per cent to 39 per cent. Looking ahead, the department will need to fill 12 new positions plus three retirements over the next four years. If it hires close to parity, over 40 per cent of faculty will be women—which matches the target for student recruitment.

“We want to hire the best,” says Mason. “That involves examining and removing historical biases held by hiring committees. Last year, we hired three women and two men—candidates equal in skills and experience—using diversity as one criteria. We need diversity in the department to offer the best possible programs. As a culture, we use too many systems today built by white males drawing on their specific socialized perspective. That’s too narrow in a world defined by a multitude of perspectives.”

Mason emphasizes that diversity in hiring is “not just a check box.” A critical question is now raised when considering candidates: “How will this person broaden our perspective on the world?” That question reaches beyond female faculty toward a department demographic that reflects that of the Greater Toronto Area.

As a 2020 hire in the department, Dr. Yeganeh Bahoo has had very different and distinct experiences of gender balance in her field. While earning her undergraduate degree in Iran, 74 per cent of students in her program were women. At the University of Manitoba for her doctorate and now at Ryerson, it’s a complete reversal.

“My view is that if we can equally support all individuals in their choices and in developing their talent, gender inequities would disappear,” says Bahoo. “Of course, we don’t live in that world and biases persist. I have heard from many exceptional female students that they don’t think they’re a good fit for computer science. We need to set a goal for ourselves throughout all of education to dismantle those biases and barriers.”

Bahoo recalls one very strong math student who believed she didn’t have what it takes to succeed in computer science but whose boyfriend was very good at it “because he plays a lot of games.” In Bahoo’s mind, a good math student is an excellent computer science candidate, period.

Bahoo is aware of the messaging all students absorb in elementary and secondary education in this country that pushes women away from the field. The more female computer scientists all students see who encourage young women to participate in academic programs, extracurricular clubs and coding competitions, the better.

It is just as important for university students to see themselves reflected in their professors so they can envision a future career in computer science. Bahoo is committed to mentoring female students at all levels and is also interested in participating in programs that bring female computer scientists to high schools, whether in person or remotely.

If there is one theme that describes the momentum behind student and faculty recruitment in the Computer Science department today, it’s correcting for historical and cultural distortions.

“Our faculty and students are building the future tools that all of society will use, so they need to reflect all of society,” says Mason. “All socialized perspectives need to be in play. Our graduates will build better systems if surrounded by more diverse thinking and experiences.”