Women in science take the lead to increase equity and inclusion in STEM

Women face challenges, both in the lab and in classrooms, as they pursue their science careers.

The underrepresentation of women in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics and computer science) fields of study is an unfortunate reality in Canada and around the world. In 2016, women made up 34% of STEM bachelor’s degree holders and 23% of science and technology workers among Canadians aged 25 to 64.

As women progress from high school to postsecondary studies and into the labour market, their representation in STEM decreases. In 2016, among Canadian-educated workers 25 to 34, 54% of women with a bachelor’s degree in computer and information sciences worked in science and technology occupations, compared with 74% of men. Likewise, women with degrees in mathematics and related studies or physical and chemical sciences were less likely than men in those fields to work in science and technology occupations, by 10 percentage points or more.

We spoke to some Faculty of Science students and faculty about the challenges and approaches to increase women's representation in science and technology.

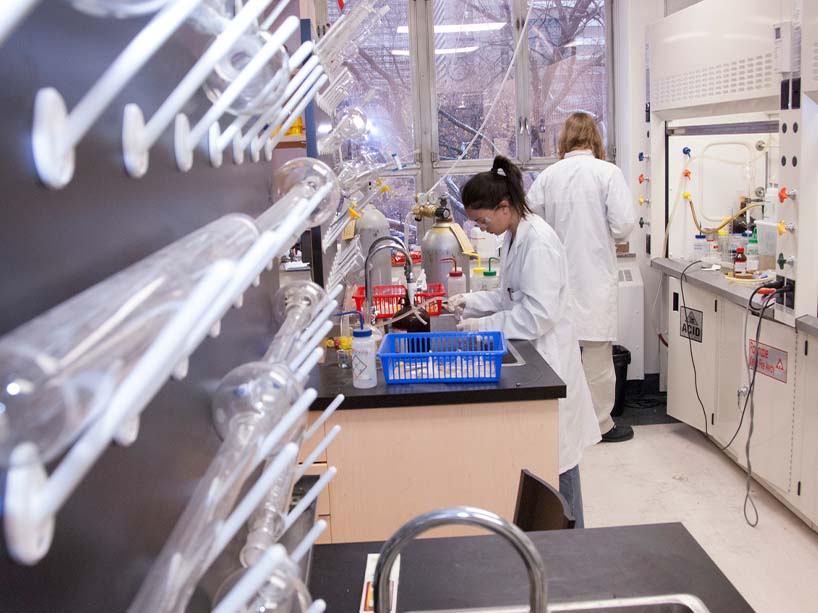

Shweta Mistry is a researcher at the Soft Matter Research and Technology (sMaRT) Lab at Ryerson.

Shweta Mistry, a PhD candidate in the biomedical physics program, recently found out she won a leadership award at the university. Instead of jumping for joy, Mistry’s first reaction was to question if she deserved it.

“I went to the person who wrote me the reference letter and told him the news. Then I asked him - am I good enough? Do I deserve this award? Should it have gone to someone else?” Mistry says.

Her initial reaction was to second guess herself, despite her impressive research and extensive involvement in extracurricular activities.

Mistry is currently pursuing a PhD in biomedical physics, with a project focused on liquid crystalline structures used for controlled drug release. She is also a graduate student representative in the self-assessment team for the Dimensions Pilot Program, part of the physics graduate student union and the Canadian Organization of Medical Physicists.

Elodie Lugez is committed to creating opportunities for women in the STEM field.

Creating more opportunities for women

For Elodie Lugez, a new assistant professor in the department of computer science, the imposter syndrome has never really gone away.

“In elementary school, I knew I wanted to become a professor in mathematics,” Lugez says. “But I never had the courage to say it out loud because I didn’t want to seem different from the other students. I’m thankful that I grew up in a supportive environment where I was encouraged to pursue my passions through many opportunities.”

Last summer, Lugez was looking to hire some students to join her lab through the career boost program. There was only one applicant who identified as a woman and she wasn’t even in the computer science department.

Lugez created a second position for this student because she wanted to give her the opportunity to participate. It turned out to be the right call and Lugez has been exceptionally pleased with the students’ work ever since.

Miranda Kirby uses feedback from her students to create open, inclusive classroom environments.

Fostering inclusive research environments

This year, Miranda Kirby, an assistant professor at the department of physics, was noticing that online engagement was lower than usual. Only a couple of male students were having discussions in the virtual environment.

Kirby enlisted the help of the whole group to identify ways to increase engagement overall. They came up with the idea to have rotating student chairs at all of their lab meetings, with one student leading the discussion each week. Kirby says this increased engagement and allowed everyone to have their voices heard.

It is important to foster a learning environment where everybody feels safe to try new things and feel comfortable expressing their opinions, Kirby says. At the beginning of every year, she hosts an orientation where she talks to students about expectations and how they will treat each other with respect.

Roxana Sühring makes an effort to highlight diverse voices in her class readings.

Showcasing women’s voices

In order to create an inclusive learning environment, Roxana Sühring, assistant professor at the department of chemistry and biology, says it is important to highlight women’s voices.

“Many wonderful and talented scientists who are women so often go unnoticed, especially those who are visible minorities,” says Sühring. “In my classes, I always make a point of highlighting that not all academics who receive the Nobel Prize look like Einstein.”

Diversity of experience and thought, she says, is what enables the best research. Sühring highlights the research of notable women and chooses examples for her undergraduate students that represent diversity of thought in the field.

Sühring argues that there needs to be a more diverse representation in science so that young women have the opportunity to see themselves in the STEM field. Diverse role models, Sühring says, are one way to help women from a broad range of backgrounds overcome the hurdle of entry into various scientific fields.

Related stories: