The Globe & Mail Is Correct: Ontario Can Learn About Housing from Alberta But Disregards the Importance of Greenfield Development

By: Frank Clayton, Senior Research Fellow, with research assistance from Yagnic Patel

November 22, 2024

(PDF file) Print-friendly version available

Executive Summary

The Editorial Board of the Globe & Mail thinks it has figured out how to alleviate the affordability challenges faced in Ontario and the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). The province should become more like Alberta. The Editorial Board's affordability solution consisting of almost all new housing being apartments, from duplexes to high-rises, built on sites in pre-existing built-up areas of Ontario cities ignores that much of Alberta's housing is ground-related dwellings, like single-detached houses and townhouses, built on greenfield land. The Editorial Board is against the development of greenfield lands.

An essential lesson from Alberta for GTA municipalities, ignored by the Editorial Board, is that they must have a plentiful supply of zoned, serviced greenfield land for new ground-related and low-rise apartments, such as stacked townhouses, in addition to densifying existing communities.[1] Otherwise, the affordability of these types of housing will continue to deteriorate. Torontonians will continue to move to other parts of the province to find more affordable ground-related homes. It is unrealistic to expect that densifying existing neighbourhoods alone will produce the quantity of ground-focused housing the market requires to improve affordability given the demand growth pressures.

A second lesson for GTA municipalities from Alberta is the need for a land use planning system more conducive to accommodating new housing development, especially on greenfield lands, to produce a range of housing types, including single-detached and semi-detached houses, townhouses and low-rise apartments, and reduce the financial burdens they are imposing on new development.

Background

The Editorial Board of the Globe & Mail thinks it has figured out how to alleviate the affordability challenges faced in Ontario and the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). The province should become more like Alberta with its faster approvals of development applications, increased permitted densities in existing single-family housing neighbourhoods, and lower development charges and related financial contributions.[2]

Undoubtedly, adopting these changes would increase the housing supply and reduce development costs, resulting in housing prices and rents in Ontario falling below what they would otherwise be. However, any impact would be significantly diluted because, as in Alberta, housing is also needed on greenfield lands adjacent to built-up areas, which the Editorial Board opposes.

The Editorial Board's vision consists of almost all new housing being apartments, from duplexes to high-rises, built on sites in pre-existing built-up areas of Ontario cities which ignores the fact that much of Alberta's housing is ground-related dwellings, like single-detached houses and townhouses, on greenfield lands.[3]

An essential lesson from Alberta for GTA municipalities is that they must have a plentiful supply of zoned, serviced greenfield land available for new ground-related and low-rise apartments, such as stacked townhouses, in addition to densifying existing communities. Otherwise, these housing types will continue to become less affordable, and Torontonians will continue to move to other parts of the province to find more affordable ground-related homes. It is unrealistic to expect that densifying existing neighbourhoods alone will produce the market's required ground-related housing.

A second lesson for GTA municipalities is the need for a land use planning system more conducive to accommodating new housing development, especially on greenfield lands, to produce a range of housing types, including single-detached and semi-detached houses, townhouses and low-rise apartments, and reduce the financial burdens they are imposing on new development. The Editorial Board mentions this lesson but only for housing in built-up areas.

Housing Affordability

Calgary and Edmonton are much more affordable than Toronto

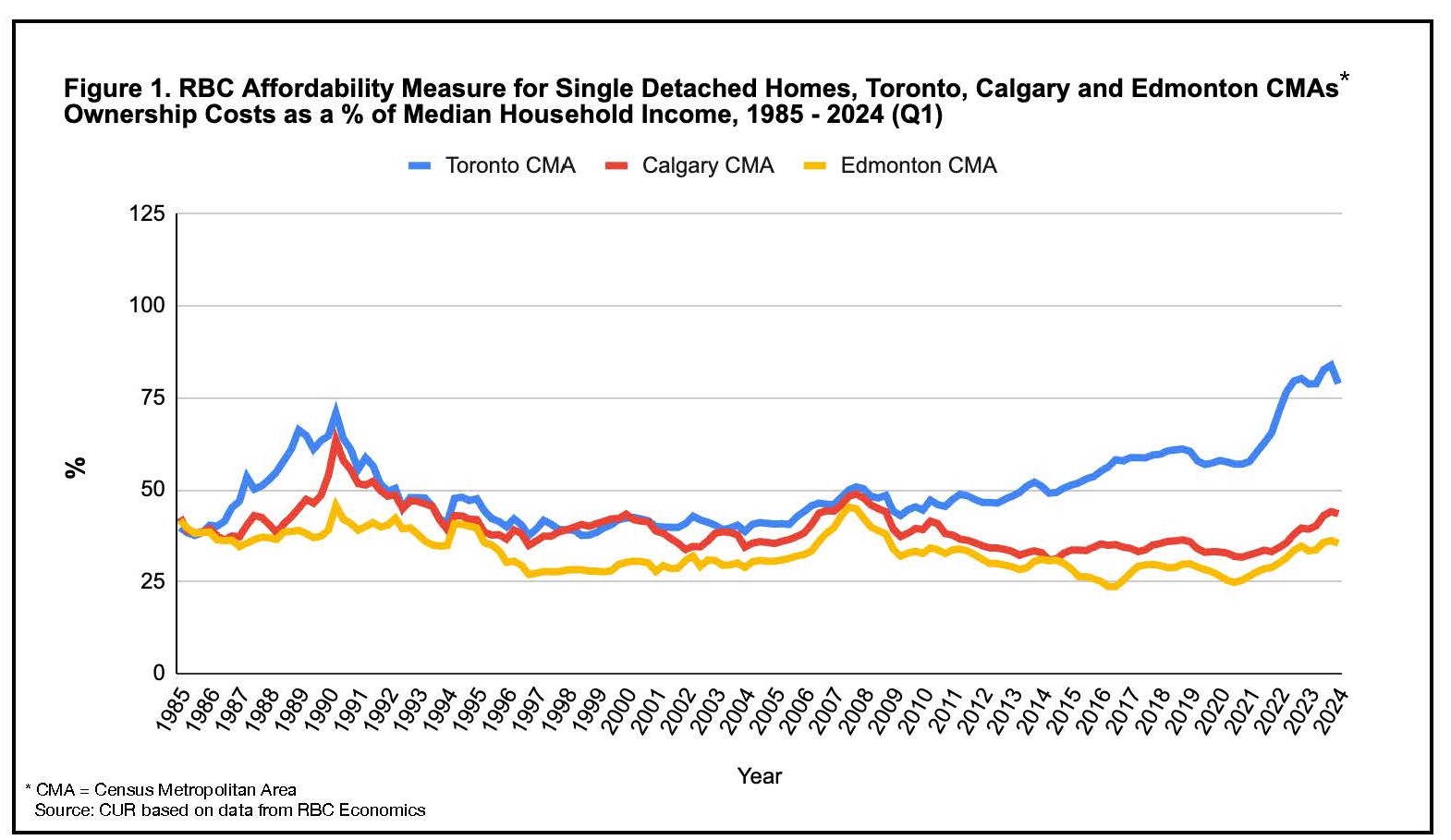

Figure 1 plots RBC's housing affordability measure for the Toronto, Calgary and Edmonton CMAs from 1985 to the first quarter of 2024.[4] This measure shows the proportion of median pre-tax household income required to cover mortgage payments, property taxes, and utilities for purchasing a single-detached house at the benchmark market housing price.[5]

Housing affordability has been more benign in Calgary and Edmonton. RBC's affordability measure in both CMAs in the first quarter of 2024 is about the same as in the mid-1980s (mid-40s percent). Toronto's experience is markedly different. Housing is much less affordable now than in the mid-1980s – 96.3% in the first quarter of 2024 vs 47.9% in 1985. Toronto's divergence from the other two CMAs has been centred on the years since 2007. Municipally constrained sites should be removed from the short-term land supply.

The Importance of Greenfield Housing Development for Affordability

A significant difference between the central cities: Toronto is built out, Calgary and Edmonton have considerable greenfield land

The city of Toronto is fully built out. It no longer has fringe vacant lands (so-called greenfield lands) for housing development. In contrast, the cities of Calgary and Edmonton have significant greenfield lands.[6] Consequently, Toronto's new housing is predominantly apartments, whereas the cities of Calgary have a broad mix of housing focusing on ground-related homes.

Ground-related housing accounts for much of the housing built in the Calgary and Edmonton CMAs - apartments dominant in Toronto

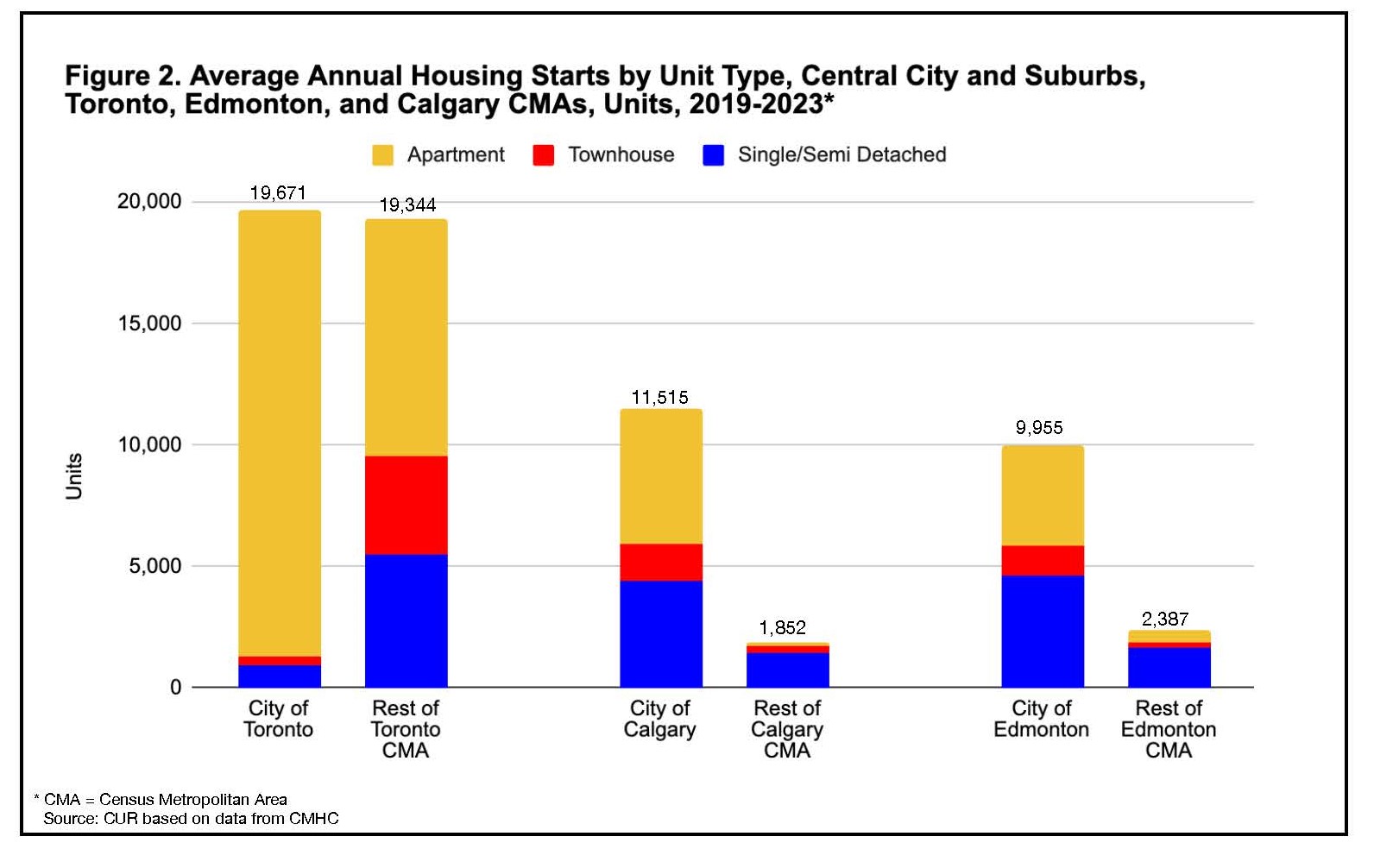

Figure 2 presents housing starts by unit type in the three CMAs, split between the central city and suburban municipalities.

As noted, the mix of housing starts between the three central cities is markedly different. Virtually all Toronto starts are apartments. In contrast, Calgary and Edmonton have a mix of starts, with singles/semis and townhouses accounting for half or more of total starts.

Interestingly, the mix of starts in the Toronto CMA's suburban municipalities is similar to those in the cities of Calgary and Edmonton.

Most new housing built in the cities of Calgary and Edmonton is ground-related housing

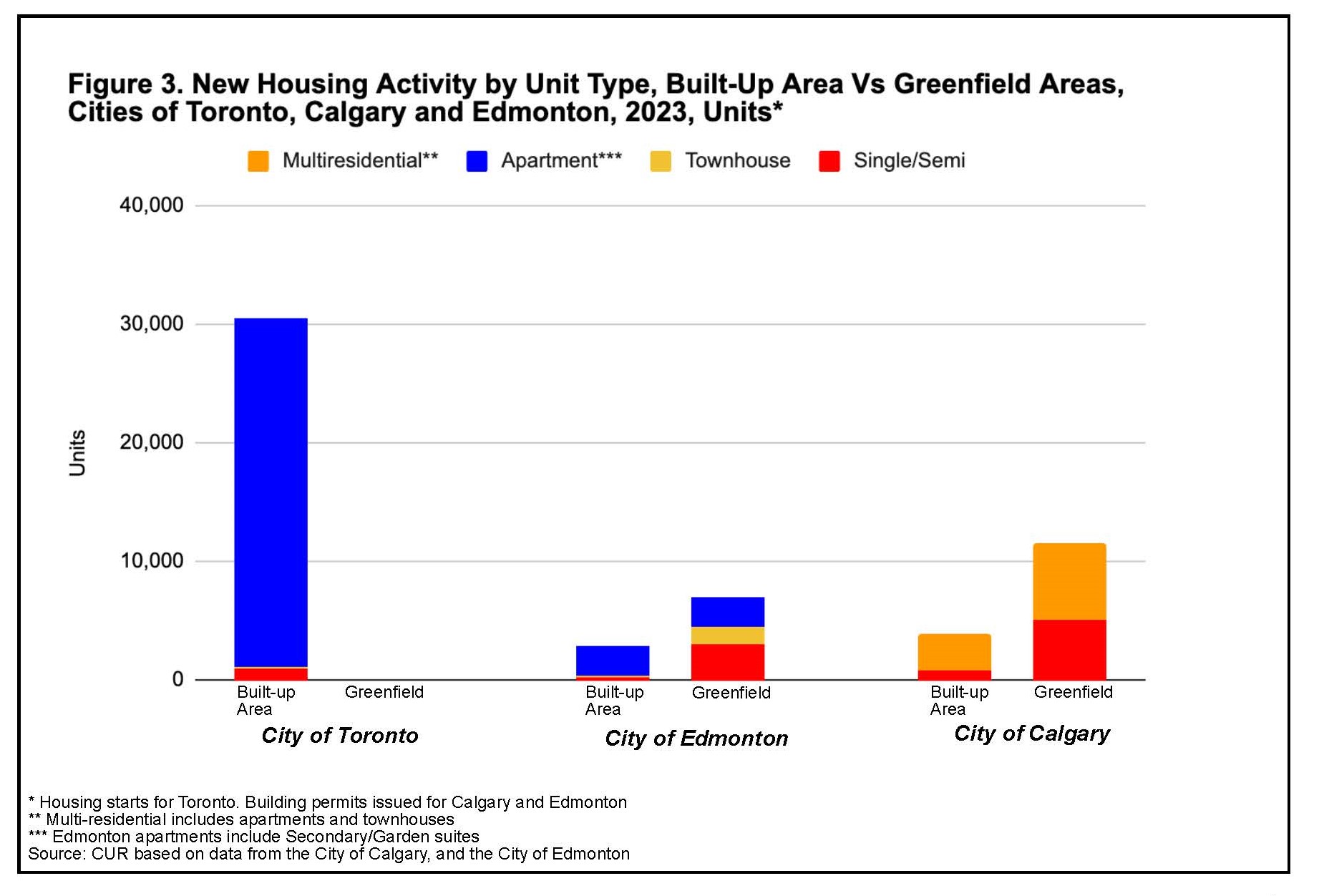

Figure 3 presents new housing activity by unit type for the built-up and greenfield areas for each of the three central cities. Some background on this figure:

- "Activity" is housing starts for Toronto and building permits issued for Calgary and Edmonton.

- What the city of Calgary calls "new communities" and Edmonton calls "developing areas" are referred to as "greenfield areas" here.

- The difference between the city of Calgary's totals and activity in "new communities" is called “built-up areas.” What Edmonton calls “redeveloping areas” is also called “built-up areas.”

- Edmonton apartments include secondary/garden suites.

- The city of Calgary combines townhouses and apartments into "multi-residential."

Since the city of Toronto no longer has greenfield areas, almost all new housing activity is apartments in the built-up area. In contrast, in the cities of Calgary and Edmonton, most new housing units are built in greenfield areas. Moreover, most new units are ground-related homes (singles, semis and townhouses).[7]

The bottom line is that greenfield development in the Calgary and Edmonton CMAs provides much of the housing built, including many ground-related homes, and the Toronto CMA needs to do more in this regard to address supply and affordability

By accommodating new housing on greenfield lands and redeveloped and intensified sites in built-up areas, Calgary and Edmonton provide an expanded opportunity to build more and a broader range of housing to accommodate the marketplace's requirements. Medium- and higher-density apartments dominate housing products in built-up areas. In contrast, lower-density housing forms like single- and semi-detached houses and townhouses are more common on greenfield lands. It is also well-documented that most households looking to buy a home want a ground-related home.[8]

The lesson for the Toronto CMA from the Alberta experience is to encourage housing to be built in both built-up areas and greenfield lands. The spectre of thousands of single-detached houses built on large lots removing vast tracts of farmland is false. Greenfield development in the GTA will blend lower-density single- and semi-detached houses, townhouses, and more affordable alternatives like stacked townhouses and low-rise garden apartments.

The Land Use Planning Process and Municipal Government Charges Are More Accommodative for New Housing in Calgary and Edmonton Than in the Toronto CMA

Planning restrictions and speed of approving new developments are more favourable to affordability in Calgary and Edmonton CMAs than Toronto

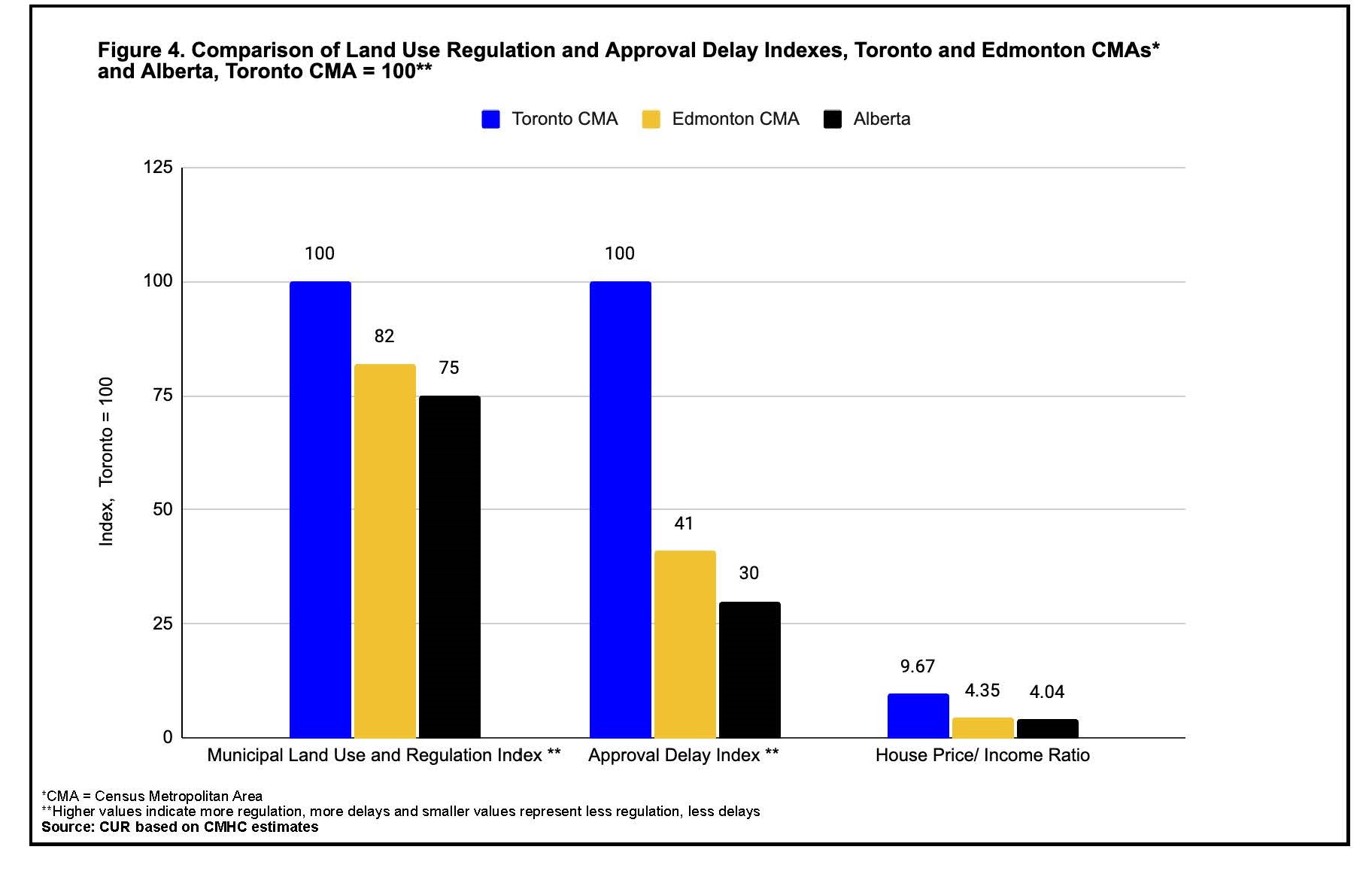

With the support of the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Statistics Canada undertook a new survey, the 2022 Municipal Land Use and Regulation Survey. This survey of municipalities obtained information on zoning, approval times, community consultation, density limits, environmental assessments, and fees for residential development in both built-up and greenfield areas. CMHC created two separate but interrelated indexes from this survey – the municipal land use and regulation index and the approval delay index.[9]

Figure 4 provides the index findings for the Toronto and Edmonton CMAs and the Ontario and Alberta provinces. The Calgary CMA was not separated in the index findings. The survey results are expressed in indexes where the Toronto CMA equals 100.

The Toronto CMA has a more restrictive planning regulatory regime and longer approval delays than the Edmonton CMA or Alberta in general. Edmonton's land use regulation index is 18% lower (less regulation), and the approval delay index is smaller by 41% (faster approvals) than that of the Toronto CMA.

The cities of Edmonton and Calgary have relatively low government charges compared to municipalities in the Toronto CMA

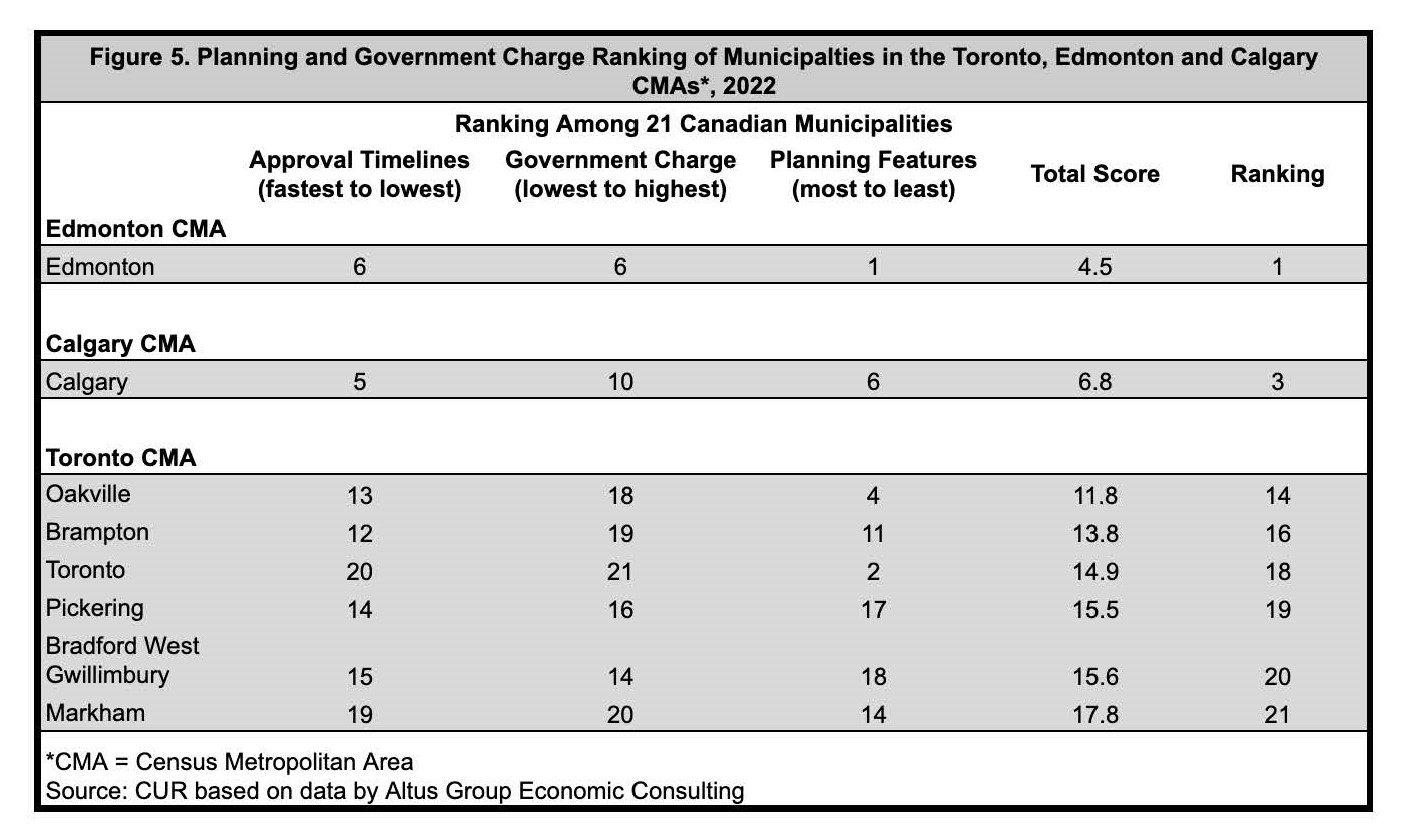

An empirical study conducted for the Canadian Home Builders Association (CHBA) confirms that the cities of Calgary and Edmonton have shorter approval times than Toronto CMA municipalities surveyed.[10] In addition, they also impose lower government charges on new residential development.[11] The study, which Altus Group Economic Consultants prepared, ranked 21 municipalities across Canada according to the composite of three planning attributes: planning features, approval timelines, and municipal government charges. The results for the three CMAs are shown in Figure 5.

The study found that government charges in several municipalities within the Toronto CMA ranked much higher than the cities of Edmonton and Calgary. Edmonton and Calgary ranked sixth and tenth out of 21 municipalities in their levels of municipal government charges. The surveyed municipalities in the Toronto CMA were at the other extreme, ranking between 14th and 21st.

The bottom line is that the planning systems in the cities of Calgary and Edmonton are more agile and impose smaller financial charges than municipalities in the Toronto CMA, which encourages more housing to be built quickly, a broader range of housing units, and aids affordability

The lesson emerging from comparing large urban areas in Alberta and Ontario is that improved housing affordability requires significantly more housing units, providing a greater variety of housing types and reducing housing production costs by lowering municipal government charges.

We agree with the CMHC economists, who found that "data collected from the 2022 Municipal Land Use and Regulation Survey unearthed a compelling connection between land use regulations and housing affordability, particularly in highly regulated cities.”[12] These economists also concluded, "cities with highly regulated land use policies often experienced a scarcity of developable land, leading to increased competition and inflated housing prices. This revelation prompted calls for a more flexible and adaptive approach to urban planning. It emphasizes the need for a balance between responsible development and affordable housing."

End Notes

[1] We label the combination of single- and semi-detached houses and townhouses as ground-related housing.

[2] Globe and Mail Editorial Board. What Ontario Can Learn From Alberta About Housing. September 23, 2024.

[3] Typically, most housing built in built-up areas are apartments. In contrast, most housing on greenfield lands are ground-related housing types (single-detached houses, semi-detached houses, townhouses) and, more recently, stacked townhouses and other forms of low-rise apartments.

[4] A census metropolitan area (CMA) represents a commutershed or housing market area.

[5] For details of the RBC affordability measure, see Robert Hague. Housing Trends and Affordability. RBC Economics. June 2024.

[6] Because the cities of Calgary and Edmonton still have substantial amounts of greenfield lands, they are more representative of a housing market area than the city of Toronto. They can accommodate a more varied range of housing types that is more affordable than comparable housing in their built-up areas.

[7] Although the city of Calgary combines townhouses and apartments in its land analysis, it is likely that most townhouses are built on greenfield lands within the city.

[8] See for example, Frank Clayton. What Kinds of Housing Are Homebuyers or Intending Homebuyers in the GTHA Choosing? CUR. June 28, 2022.

[9] CMHC. Municipal Land Use and Regulation Survey Results. The Housing Observer. July 13, 2023.

[10] Altus Group Economic Consulting. CHBA National Municipal Benchmarking Study. CMHC. October 17, 2022.

[11] Government charges imposed by municipalities include infrastructure costs (development charges in Ontario), planning and approval fees, parkland contributions, land transfer taxes (Toronto), community benefits charges (Ontario), and density bonusing.

[12] CMHC. A Comprehensive Retrospective of CMHC Housing Reports: What We Learned in 2023. December 20,2023.

References

Altus Group Economic Consulting (2022). ‘Canadian Home Builders’ Association National Municipal Benchmarking Study.’ CMHC. October 17, 2022. [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://st.chba.ca/CHBADocs/CHBA/HousingCanada/Government-Role/2022-CHBA-Municipal-Benchmarking-Study-web.pdf (external link)

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (2023). ‘Municipal Land Use and Regulation Survey Results: Approval Delays Linked with Lower Housing Affordability.’ The Housing Observer. July 13, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/blog/2023/approval-delays-linked-lower-housing-affordability (external link)

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (2023). ‘A Comprehensive Retrospective of CMHC Housing Reports: What We Learned in 2023.’ December 20, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/blog/2023/comprehensive-retrospective-cmhc-housing-reports (external link)

Frank Clayton (2022). ‘What Kinds of Housing Are Homebuyers or Intending Homebuyers in the GTHA Choosing?’ CUR. June 28, 2022. [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://www.torontomu.ca/content/dam/centre-urban-research-land-development/CUR_Preference_Homebuyers_Intending_Hombuyers_GTHA_June_2022.pdf

Globe and Mail Editorial Board (2024). ‘What Ontario Can Learn From Alberta About Housing.’ September 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/editorials/article-what-ontario-can-learn-from-alberta-about-housing/ (external link)

Robert Hague (2024). ‘Housing Trends and Affordability.’ RBC Economics. June 2024.