Guelph Has an Insufficient Supply of Short-Term Residential Land: Time for Municipalities to Correctly Measure Their Short-Term Land Adequacy

By: Frank Clayton, Senior Research Fellow, with research assistance from Yagnic Patel

October 17, 2024

(PDF file) Print-friendly version available

Executive Summary

This blog examines a recent analysis of the current supply of short-term land for housing and its adequacy as prepared by the City of Guelph's planning staff. The City’s report contains extensive information on the short-term land supply, including sites with municipally imposed constraints. Land supply adequacy follows provincial policies about minimum short-term residential land supply needs - except the City, like many municipalities, misinterprets the Province’s policies.

The City report calculates that the City of Guelph has a 6.2-year supply of short-term residential land (for all types of housing combined), double CUR’s calculation of 3.1 years. For ground-related housing (singles, semis, and townhouses), we estimate the supply is even less—2.5 years. Thus, the City’s short-term land supply is significantly below the Province’s policy of a minimum supply of four years (based on maintaining a three-year supply at all times with annual monitoring).

We calculate that Guelph has a shortfall of short-term residential land equivalent to 708 units of ground-related housing (291 singles and semis and 417 townhouses) and a shortfall of short-term sites for apartments of 454 units.

Remember that this shortfall is based on the minimum years of supply required by the PPS. Municipalities should target higher years of supply to accommodate household growth, provide market competition, and compensate for past years of underproduction.

We recommend that the province adopt the template described in the blog so municipalities can consistently calculate the adequacy of their short-term land supply by unit type.

Background

This blog examines a recent analysis of the current supply of short-term land for housing and its adequacy as prepared by the City of Guelph's planning staff.[1] The report provides abundant housing information, especially details of the City's short-term residential land supply. The City's transparency in this regard is a model for Ontario municipalities in general to follow. Let's hope that they do.

The report calculates that Guelph meets the short-term land requirement of Policy 1.4.1 b) of the 2020 Provincial Policy Statement (2020 PPS) since it has enough short-term land to supply 6.2 years of new housing. This finding would be laudable if true, but it is not. We calculate that the City has a significant shortfall of short-term land for new ground-related housing, with just 2.5 years of supply and an overall supply, including apartments, of 3.1 years. As we explain later, municipalities like Guelph are expected to have a minimum of a 4.0-year supply of short-term residential land by unit type with annual monitoring and should target an even greater supply to promote a competitive housing market and make up for past underproduction.

Hopefully, planners in other municipalities will review this blog and adjust how they calculate the years of supply of short-term residential land to make it meaningful and more effective for increasing housing. Also, if the Province reviews the blog, they will understand that municipalities need a method for using a clear and accurate template to assess short-term supply.

How the City calculated the adequacy of its short-term land supply

- It starts with the relevant policies (1.4.1 and 1.4.1 b) in the 2020 Provincial Policy Statement (2020 PPS)[2]:

"Policy 1.4.1 - To provide for an appropriate range and mix of housing options and densities required to meet projected requirements of current and future residents of the regional market area, planning authorities shall:

b) maintain at all times where new development is to occur, land with servicing capacity sufficient to provide at least a three-year supply of residential units available through lands suitably zoned to facilitate residential intensification and redevelopment, and land in draft approved and registered plans."

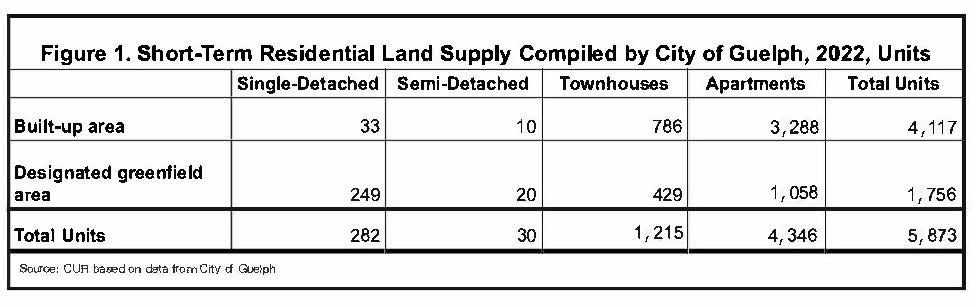

- It tabulates the City's short-term residential land supply.

The information provided is detailed. The total short-term land supply is disaggregated by dwelling type (single-detached, semi-detached, townhouses, and apartments). Short-term land supply is also provided by component: units by type in draft-approved plans of subdivisions, in registered plans of subdivisions (presumably on unbuilt sites), and zoned sites outside of plans of subdivisions (presumably these are sites in the City's built-up area). Lastly, statistics are provided by housing type on short-term sites with additional municipal-imposed constraints (these sites are likely to be delayed coming to the marketplace).

The City calculates the years of supply using the total short-term land supply, including constrained sites.

- The average annual total requirement for new housing is presented.

The long-term average growth in households up to 2051 is shown. It is attributed to the City's updated growth management strategy.[3]

- Years of supply for the short-term land supply is calculated by dividing the total short-term land supply (all housing types) by the household average annual long-term growth (to 2051).

Here is the calculation behind the finding that the City has 6.2 years of supply of short-term land:

Short-term land supply = 5,873 units

Average annual requirements = 947 units

Years of supply = 6.2 years (5,873/947)

The analysis concludes: “In 2023, Guelph had enough available land to supply 6.2 years of housing on land that is zoned with servicing capacity (referred to as short-term housing supply), which meets the Provincial Policy Statements’ housing supply requirement of policy 1.4.1 b) which requires municipalities to maintain at least a three-year supply of residential units on lands that are zoned with servicing capacity” (p. 19).

How the City should have calculated the adequacy of its short-term residential land supply

Many municipalities calculate the adequacy of their short-term land supplies in a way identical to Guelph's. I'm afraid that's not right. It does not address the purpose of the policies in the 2020 PPS, which is to ensure ample sites are readily available in municipalities to meet the short-term housing requirements by unit type. Let's illustrate how the years of short-term land supply should be calculated using the Guelph analysis.

Short-term land supply should be compiled by unit type, encompassing greenfield and built-up area sites.

Like several other municipalities, Guelph compiles its short-term land supply by unit type. The unit types utilized are the same as those utilized by CMHC in its starts and completions survey: single-detached houses, semi-detached houses, townhouses, and apartments.[4] Singles and semis are often combined since smaller lot singles are replacing semis in the new housing marketplace.

Other unit variations are desirable. We often combine singles, semis and townhouses, calling them ground-related housing. With the increased interest in missing middle housing, it makes sense to disaggregate apartments into duplexes, stacked townhouses, and low-rise, mid-rise, and high-rise apartments.

Guelph correctly compiled its short-term land inventory for its designated greenfield areas and built-up areas - unlike other municipalities that often consider only greenfield land.

The City's short-term land supply could accommodate 5,873 units. Apartments account for almost three-quarters of the City's short-term land supply, followed by townhouses at about 21%. Just 5% of the land supply consisted of sites for singles and semis.

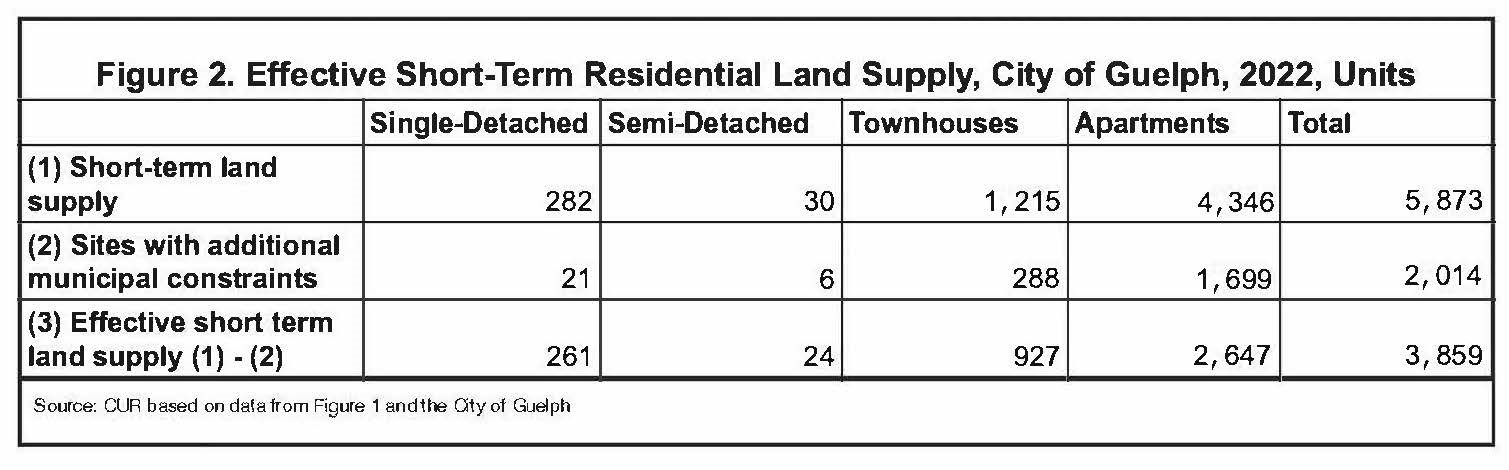

Municipally constrained sites should be removed from the short-term land supply.

Guelph is to be commended for identifying sites with additional municipally imposed constraints[5]. These constraints cast uncertainty on when the sites will be available for new housing construction. Since there is uncertainty about these sites' availability to meet housing requirements in the short term, they should be excluded from the short-term land supply.

Figure 2 shows the housing units by type on municipally constrained sites and the short-term land supply when these units are excluded, which we label as effective short-term land supply.

About a third of the City’s short-term land supply consists of sites with additional municipally imposed constraints. Apartments are most affected by these constraints.

The City of Guelph’s report describes three sites that make up 78% of the short-term lands with additional municipal constraints. One site consists of apartments approved in 2014, where the developer must build expensive infrastructure before constructing 350 units.

Average annual short-term housing requirements should be broken down by unit type.

Many municipalities, including Guelph, look at the total housing requirements even though the 2020 PPS (and the new 2024 PPS) clearly state that municipalities are to provide an “appropriate range and mix of housing options and densities.” In addition, Guelph applies the average long-term housing requirements to the short-term supply of land, understating the requirements expected over the short term. Guelph applies a long-term average of 947 units per year, representing the average annual requirements over the 2022-2051 period.[6]

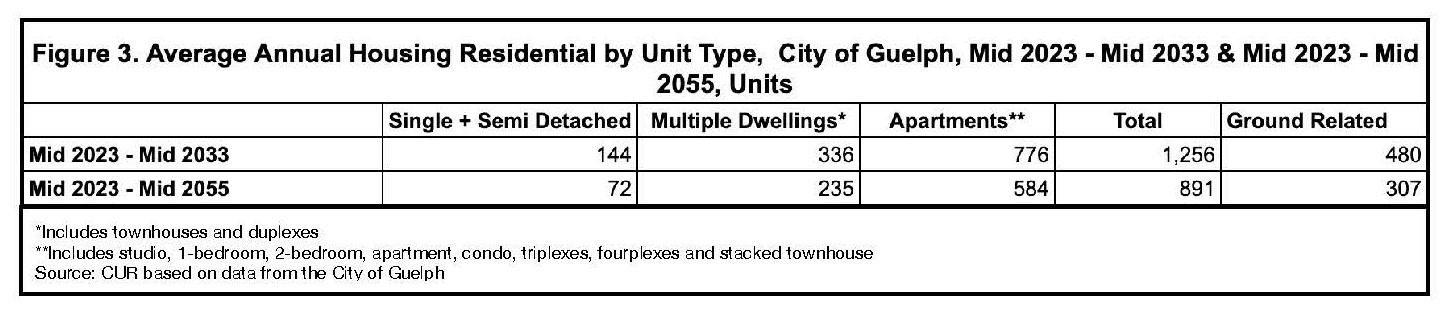

Guelph's 2023 Development Charges Background Study (DC study) provides the most recent forecast of housing requirements by unit type.[7] Figure 3 shows the study’s housing requirements for the short-term (mid-2023-mid 2033) and long-term (mid-2023-mid 2055).

Two features in the forecast should be examined:

- The average long-term growth is 891 units per year in the DC study vs. 947 units in the City’s land adequacy analysis.

It is not clear why the growth in the DC study is lower, but it may exclude students who are not classified in the Census of Canada as permanent residents of Guelph.

- The DC study’s average annual short-term forecast is significantly higher than its long-term forecast.

The short-term annual average requirement of 1,256 units between mid-2023 and mid-2033 is 41% higher than the City’s long-term average of 891 units. By utilizing the long-term average in its short-term land adequacy calculation, the City significantly understates requirements.

The corrected calculation of years of supply of short-term land.

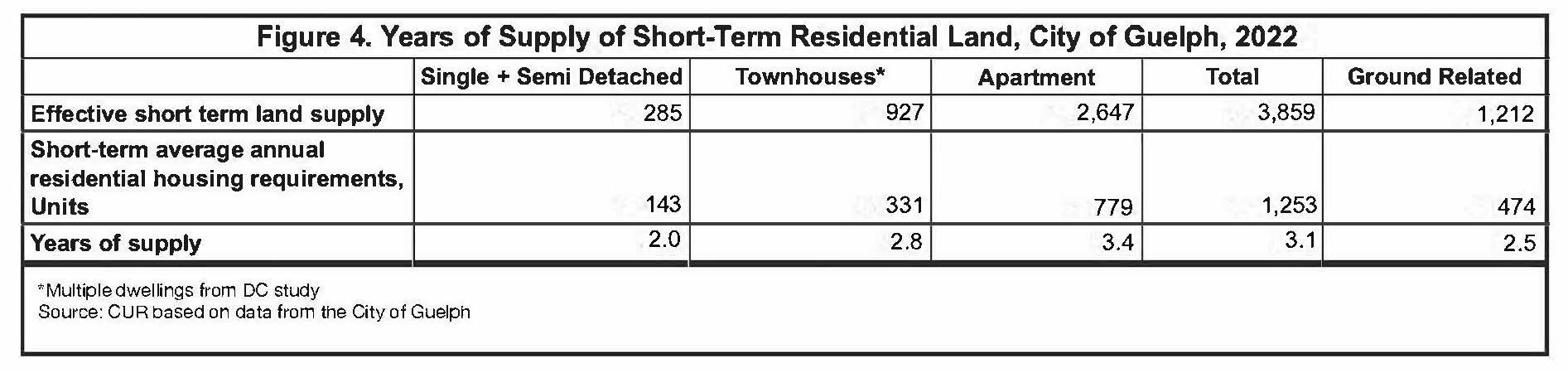

Here, as presented in Figure 4, we calculate the years of supply of short-term land by dividing the effective short-term land supply (Figure 2) by the average annual short-term requirements by unit type (Figure 3).

The corrected calculations show differing years of supply by unit type ranging from a low of 2.0 years for single and semi-detached houses to 3.4 years for apartments. The years of supply for ground-related homes (singles, semis and townhouses) is 2.5 years.

For all housing types combined, the years of supply is now 3.1 years compared to the 6.2 years calculated by the City.

The 2020 PPS benchmark requires a minimum of four years of short-term land - not three years - with annual monitoring.

I am amazed at how municipalities and even the province misinterpret the requirements of the 2020 PPS (which also applies to the 2024 PPS).

Firstly, three years of short-term land supply is frequently regarded as a target, not a minimum. Initial research we have done suggests the target should be at least six years if the goal is to keep housing prices rising at less than the inflation rate.[8]

Secondly, the policy requires municipalities to always maintain at least a three-year supply of short-term land. With annual monitoring, which is what Guelph is doing, this means a minimum of four years of short-term land, not three years, to satisfy the 2020 PPS policy (and the 2024 PPS policy).

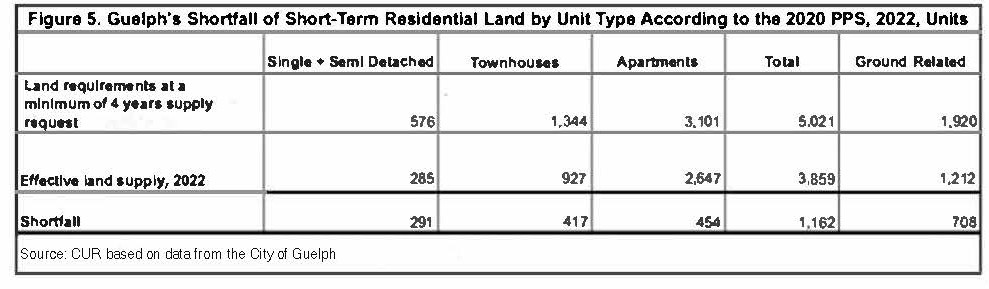

Quantifying Guelph’s shortfall of short-term land by unit type, assuming a minimum supply of four years

Figure 5 presents the calculation of short-term land requirements by unit type, assuming Guelph was targeting a minimum of a four-year supply of short-term land at the time of annual monitoring. This land requirement is subtracted from the actual supply to estimate the shortfall by unit type.

We calculate that Guelph has a shortfall of short-term residential land equivalent to 708 units of ground-related housing (291 singles and semis and 417 townhouses) and a shortfall of short-term sites for apartments of 454 units.

Remember that this shortfall is based on the minimum years of supply required by the PPS. Municipalities should target higher years of supply to accommodate household growth, provide market competition, and compensate for past years of underproduction.

We recommend that the Province adopt the template described in the blog so municipalities can consistently calculate the adequacy of their short-term land supply by unit type.

End Notes

[1] Planning Services, City of Guelph. Growth Management and Affordable Housing Monitoring Report 2023.

[2] The 2020 PPS has been replaced with the 2024 Provincial Planning Statement (2024 PPS). Policies 1.4.1 and 1.4.1 b) are now policies 2.1.4 and 2.1.4 b) in the 2024 PPS. These policies in the two documents are the same except the phrase “to facilitate residential intensification and redevelopment” has been removed in policy 2.1.4 b).

[3] We could not locate the source of this exact number.

[4] Apartments include duplexes and stacked townhouses in addition to units in apartment structures.

[5] Examples of municipal constraints include brownfield sites that require remediation and sites with zoning holding provisions that must be satisfied prior to development of the sites.

[6] City of Guelph. Growth Management Strategy and Land Needs Assessment Report, Shaping Guelph: Growth Management Strategy. December 2021. Table 3.2 shows household growth of 27,300 between 2020-2051 which translates into average annual growth of 942 households, five different than the City’s average annual household growth.

[7] Watson & Associates. 2023 Development Charges Background Study: City of Guelph. September 27, 2023.

[8] Frank Clayton and Nicola Sharp. Greater Golden Horseshoe Short-Term Residential Land Adequacy Report Series. March 2, 2017. Overview Report No. 1. March 2, 2017.

References

City of Guelph (2021). ‘Growth Management Strategy and Land Needs Assessment Report. Shaping Guelph: Growth Management Strategy.’ December 2021.

City of Guelph Planning Services (2023). ‘Growth Management and Affordable Housing Monitoring Report 2023.’ [Online]. Available: https://pub-guelph.escribemeetings.com/filestream.ashx?DocumentId=52104 (external link)

Frank Clayton and Nicola Sharp (2017). ‘Greater Golden Horseshoe Short-Term Residential Land Adequacy Report Series. Overview Report No. 1.’ March 2, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.torontomu.ca/centre-urban-research-land-development/publications/short-term-residential-land-adequacy/

Government of Ontario (2020). ‘Provincial Policy Statement, 2020.’ [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://files.ontario.ca/mmah-provincial-policy-statement-2020-accessible-final-en-2020-02-14.pdf (external link)

Government of Ontario (2024). ‘Provincial Planning Statement, 2024.’ [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://www.ontario.ca/files/2024-08/mmah-provincial-planning-statement-en-2024-08-19.pdf (external link)

Watson & Associates Economists Ltd. (2023). ‘2023 Development Charges Background Study – Consolidated Report: City of Guelph.’ September 27, 2023. [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://guelph.ca/wp-content/uploads/Guelph2023DCReport-ConsolidatedReport.pdf (external link)