City of Toronto's Economic Success Poses a Conundrum for Province's "Growth Plan"

By: Frank Clayton

February 9, 2018

This blog entry discusses the implications of Toronto’s economic resurgence for the Province’s Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe (Growth Plan) passed by the legislature in July 2017.

The Province of Ontario has created a comprehensive land-use plan that directs where population and employment growth is to occur up to the year 2041 throughout the vast area it dubs the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH), a geography encompassing nine metropolitan regions as defined by Statistics Canada. Schedule 3 of the Growth Plan provides population and employment forecasts for the years 2031, 2036 and 2041 for each of the 21 upper-tier and single-tier municipalities in the GGH.

Our analysis focuses on the economic heartland of the GGH, the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA) which includes the cities of Toronto and Hamilton and the regions of Peel, Halton, York and Durham.

These municipalities are required to apply the Ontario Growth Plan forecasts for planning and managing growth out to 2041, the horizon year of the plan (Policy 5.2.4.2).

Why are we raising this issue regarding the municipal forecasts for the year 2041 in the Growth Plan? According to a study just released by the city, Toronto has already exceeded the Growth Plan’s 2031 employment forecast and is likely to reach the 2041 forecast before the year 2021 (Toronto DC study)1. This study also finds that employment in the GTHA is generally on track to meet the Growth Plan’s 2041 forecast for the overall region. In other words, the share of regional employment attracted to the city of Toronto is growing much more than expected.

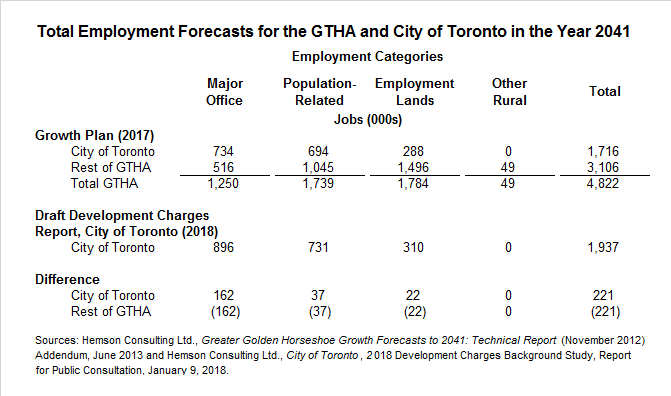

These two findings indicate that employment growth in other parts of the GTHA is underperforming the Growth Plan forecasts. This is demonstrated by the table below comparing the employment forecasts in the Growth Plan and the Toronto DC study for 2041.

The DC study forecast for Toronto’s total employment in 2041 is 221,000 higher than the forecast in the Growth Plan and, according to the Toronto DC study most of this growth has already occurred. Correspondingly, Hamilton and the 905 regions together will experience a shortfall of 221,000 employees from the Growth Plan forecasts given the Toronto DC study’s finding “…the total GTHA employment forecast is generally on track to meet the total 4.8 million jobs by 2041 forecast under Schedule C…”.

The Toronto DC study finds that the pattern of GTHA employment growth is much more centralized than forecasted in the Growth Plan because of what has been happening in downtown Toronto2. In particular, Toronto’s success in attracting major office jobs (jobs in office buildings of 20,000+ square feet) appears to be at the expense of other parts of the GTHA. These facts put a fundamental precept of the Growth Plan - creating “complete communities” throughout the GGH – in question.

Complete communities as envisaged by the Growth Plan “…provide a balance of jobs and housing in communities across the GGH to reduce the need for long distance commuting” (p. 10). Jobs in office buildings are the key to successful complete communities. Yet with the latest Growth Plan less than a year old its distribution of employment growth between the city of Toronto and the rest of the GTHA is in question, primarily because of the centralization forces for office development, which were well known before the 2017 Growth Plan was enacted.

Planning for long-term infrastructure is also problematic given the variation between where the Growth Plan says job growth should take place and where market forces are attracting the jobs. For example, Metrolinx has been instructed to utilize the population and employment forecasts in the Growth Plan in formulating its 2041 regional transportation plan for the GTHA.3 The transit plan is therefore planned for where the Province hopes where jobs would be created, not where they are being added.

To mitigate this disruption of a key pillar of the Growth Plan, the Province has limited options including: (a) directing the City of Toronto to stop approving rezonings for further office building development or (b) accepting that the Growth Plan forecasts and vision have to be revised and to do so. In other words, the Province has to decide whether to incorporate economic reality into its regional planning for the GTHA and the larger GGH.

If the Province accepts Toronto’s updated employment forecast, it casts doubts on its latest proposed directive to upper tier and single tier municipalities in the GGH. In its December 2017 discussion paper, Proposed Methodology for Land Needs Assessment in the Greater Golden Horseshoe, the Province proposes an approach to forecasting land needs that municipalities will be required to follow to forecast employment growth and land needs by type of job and by locations within their boundaries up to the year 2041. The document instructs municipalities: “in this step it will be assumed that all municipalities will achieve the employment forecast in Schedule 3 to the Growth Plan horizon”. This of course will not happen.

What the comparison of the Growth Plan and Toronto DC study’s long-term employment forecasts reinforces is the impossibility of forecasting the future precisely as the Growth Plan presumes not only for the region as a whole but for each upper-tier and single-tier municipality. There is a need for considerable flexibility when making long-term forecasts and for continuous scrutiny of emerging differences between actual and forecast growth and their economic and market impacts.

_________________________________________________________________________

(1) Hemson Consulting Ltd., City of Toronto 2018 Development Charges Background Study, Report for Consultation, January 9, 2018, pp. 67-68.

(2) If by chance downtown Toronto was able to attract larger new employers like Amazon’s HQ2, this would result in even more centralization in major office growth.

(3) Metrolinx, Draft 2041 Regional Transportation Plan for the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, September 14, 2016, pp. 16. and 32-33. Metrolinx’s methodology did examine the implications of two alternative scenarios but the recommended plan is one that is in conformity with the Growth Plan.

Dr. Frank A. Clayton is Senior Research Fellow at Toronto Metropolitan University’s Centre for Urban Research and Land Development (CUR) in Toronto.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________