Q&A with Priya Kumar

A chance conversation at a conference changed everything for Priya Kumar, CERC Migration’s newest Research Fellow to join its Data and Methods Lab. CERC Connections spoke with Priya to learn how she became interested in combining social network analysis with digital qualitative research methods and how she intends to contribute to research at CERC Migration.

How did you develop an interest in using social media as your primary methodology for research?

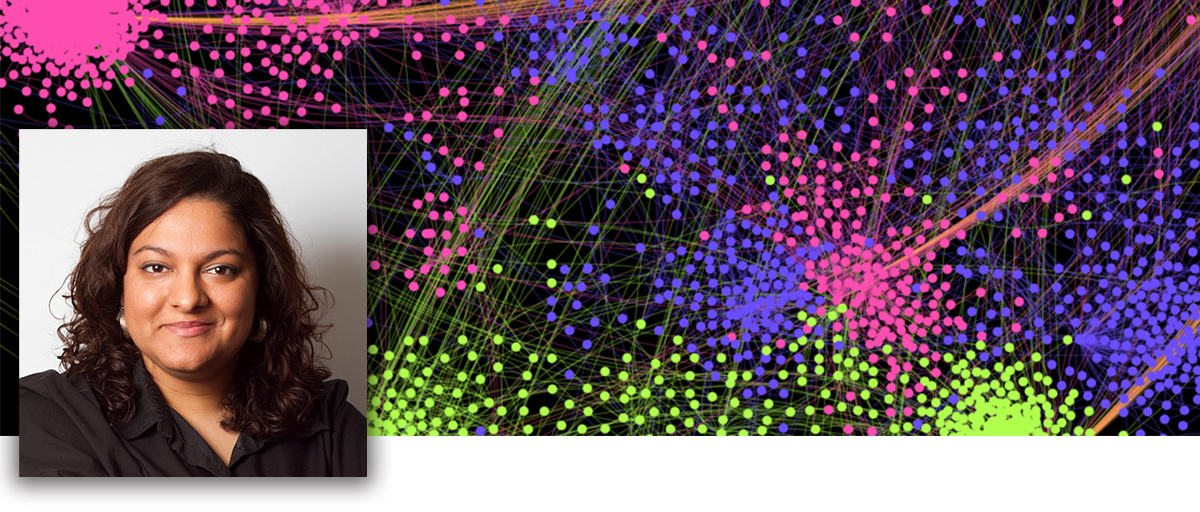

In the first month of starting out in my PhD at the SOAS University of London, I went to a migration conference on a whim, only having just started my own research. I had an enlightening conversation with members of the e-Diasporas Atlas team (Fondation Maison des Sciences de l’Homme ICT Migrations) who introduced me to digital methods and network analysis as a technique for migrant research. As a member of the e-Diasporas Atlas project, I was able to produce network graphs of migrant websites, providing a more granular view of internal community dynamics, competing narratives and agendas between diasporic actors.

After my PhD, I joined the Social Media Lab at Ryerson’s Ted Rogers School of Management. As a postdoctoral researcher, I focused broadly on how online communities connect, behave and engage on social media. And while not entirely focused on migrants at that time, I found myself relating this new field to my primary research interest on “imagined” communities. I have now collaborated with fellow colleagues on a wide variety of social media projects, from questions of data privacy, platform affordances, gender-based online violence and even diasporic national webs.

Why is social media important for understanding diaspora communities?

Diaspora communities are mobilizing, organizing and communicating differently in the digital age. These networks are using the online space for political mobilization around grievances, but also for artistic expression, cultural identity, religious congregation and for connecting to other kinds of community initiatives that don’t always have an exact “offline” counterpart. By analyzing social media, we can see local patterns, but more broadly, how diasporas are being reconstructed and mobilized.

What insights from your research have had the most influence on your work?

The most influential to me is seeing the prominence of language and diasporic discourse connected to human rights. My research showed that despite differences in migration patterns, diaspora communities (forced or voluntary) use human rights frames strategically, for solidarity and to provoke change. Communities, despite their differences – whether they have unresolved historical traumas, are working through generational traumas, or are dealing with more contemporary challenges such as integration – express grievances through the discourse of human rights.

In the Canadian context, recent social media data shows patterns of cultural expression and community representation commonly promote religious freedom, specifically to protect articles of faith. Different migrant communities will often come together on social media to express their views on questions of diversity, especially in times of crisis. As a researcher, I am interested in online conversations around religious freedoms because they offer a partial snapshot into public debates around integration and what it really means today: how are local contexts discussed, what language or key terms are being used, how are certain groups perceived by online audiences – and the challenges that lie ahead for Canadian public life.

What direction do you see your research taking as you contribute to the work at CERC Migration?

I will be interested in examining the Canadian context more. There are many issues and challenges that Canadian researchers need to look at, especially when we think about what integration needs to be today. The conversations on social media are a great starting point. For example, we now see there is a rise in newcomers looking for services online; we see lots of questions pertaining to visas and immigration on Reddit. We see a lot of discussion and questions on how digital technology is being used in refugee border lands, and we are coming to understand how important internet access, smartphone technologies and apps are for refugee and migrant communities. There are many opportunities to fuse more computational social science skills with my own passion project – which is always the diaspora and integration question.

I am also interested in how younger diasporic generations and content creators use social media to perform identity. For example, they express solidarity with historical grievances or homeland issues, share art, post live updates of events and, interestingly, the “imagined community” becomes even more important. Younger teenagers are putting two flags on their Instagram profiles. There is active promotion, an expression of identity, a symbolic act that makes these few taps on a screen a connection to one’s ancestry. Keep in mind, many of these young people are third- or fourth-generation Canadian and may have never taken a trip “back home” with their family. These online behaviours are also indicative of a new “hyphenated” Canadian identity that does not shy away from diversity.

When we each consider how much of our daily lives is shared through our social media, you realize the enormous potential for this data to reveal what matters most to individuals. Perhaps, through the CERC, we can hold up a mirror to the issues of integration and help people everywhere to better understand what it’s like to be a migrant.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.