Brampton: The Land of Secondary Suites

By: Diana Petramala and Ryan Kyle

January 13, 2022

(PDF file) Print-friendly version available

Most new additions to the housing stock are counted by CMHC in its new residential housing starts and completions survey. But there are also housing units created in the existing housing stock through the addition of secondary suites and laneway housing to existing structures and through the conversion of commercial buildings like office buildings to residential use. Units are also lost from the existing housing stock through demolitions and deconversions (removing an apartment or two from an existing structure), for example when a home with multiple apartments is torn down and replaced with a single-family house (any housing typology with one dwelling unit). The data for the number of units created or lost in the existing housing stock are available through the CMHC conversion survey. (external link)

In this blog, we use the data to look at how the existing housing stock changed in municipalities across the Toronto CMA through new additions, deconversions and demolitions between 2019 and 2021.

The data explained

Figure 1 includes housing starts data for units created and units lost through renovations and demolitions in the existing housing stock from 2019 to 2021.1

Units created in Figure 1 are calculated as all new units added to an existing structure, such as the creation of a legal secondary suite (a basement apartment), a laneway home, and/or additional apartments added to triplexes or multiplex housing.

Units lost include the complete demolition of residential housing and the removal of a unit from an existing structure (deconversion), including the tearing down of a house, whether it be a single-family home or a multi-family dwelling or the loss in units from the conversion of a three-apartment home into a single-family home.

Net new units is the difference between the additions and the demolitions.

An example of a deconversion would be a couple who purchased a home with three apartments in the city of Toronto and who have then renovated it into a single-family home. The net change in the housing stock from this project would be net loss of two units!

Three interesting facts from the data

When digging through the data we found contrasting trends in the city of Toronto and Brampton to be interesting. There were very little conversions/deconversions in the rest of the CMA:

- The negative net new units for the city of Toronto between 2019 and 2021 so far means that there is more renovation activity in which homes with multiple apartments are being torn down and replaced with single-family dwellings (as in our example above), than vice versa. The city lost almost 2,000 units from its existing stock between 2019 and 2021;

- The large net new units for Brampton shows the opposite has been true during this time. Brampton is on track to add almost 6,000 units to its housing stock by way of adding secondary suites and accessory dwellings to its existing stock in 2021, up from 3,400 in 2020 and 1,600 in 2019. It is estimated that Brampton will add more secondary suites than new homes in 2021; and

- Outside of these two extreme cases, the housing stock remained basically static across the rest of the Toronto CMA. No other municipality had anything to report.

Data limitations

The data findings are interesting indeed, but they don’t necessarily tell the whole story.

CMHC relies on building permit data available from Statistics Canada (which is ultimately provided by the municipality) to identify projects. These data would not capture apartments added without a building permit, such as illegal basement apartments. These data may, therefore, underestimate the number of new secondary suites. Brampton in particular has a very large stock of illegal basement apartments.

In addition, some municipalities, such as the city of Toronto, do not require a permit to remove apartments from a structure. In the example above, the couple would not need a demolition permit to remove the three apartments. They would only need a building permit to reconstruct the single-family home. Therefore, it is unclear how such projects would be counted in the CMHC data, and the net losses could potentially be greater.

Conclusion and implications

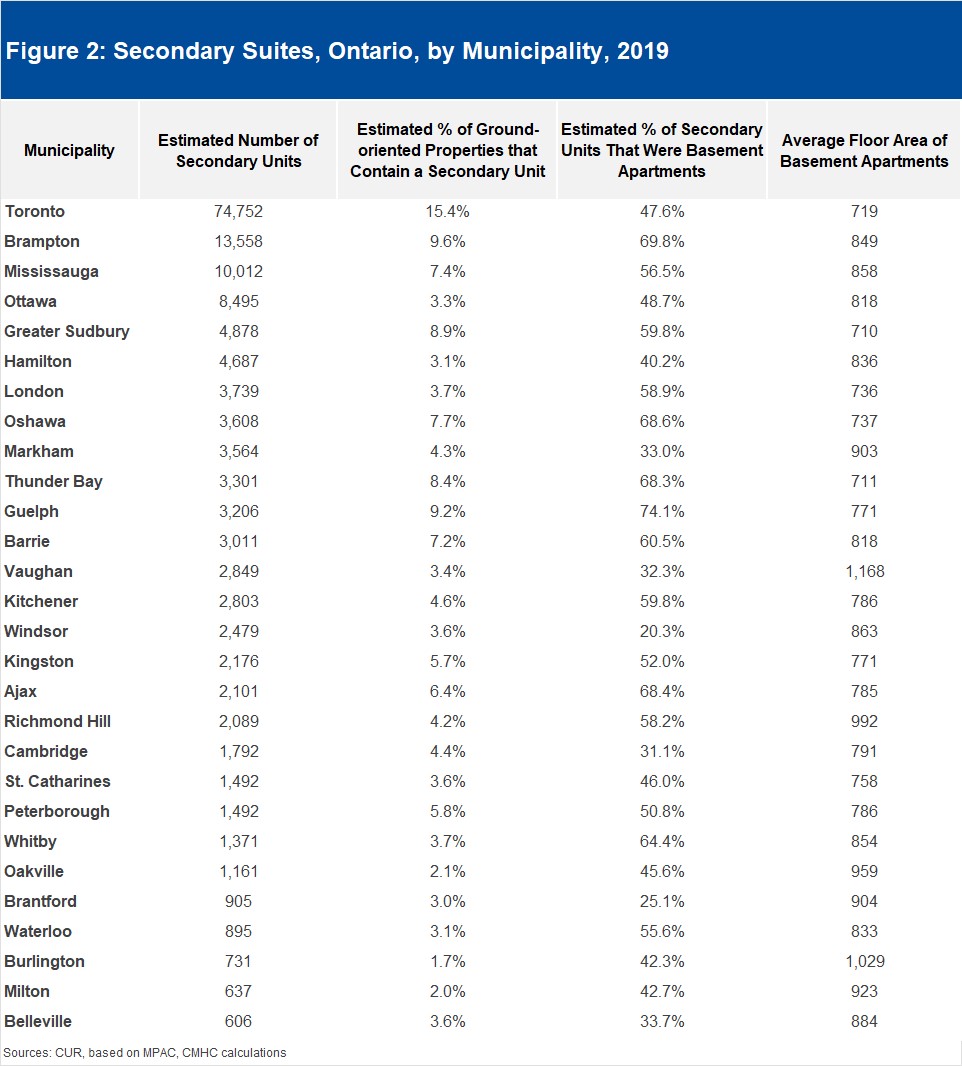

Despite the data limitations, the trends of skyrocketing construction of secondary suites in Brampton, already home to the second-largest stock in Ontario, appears to be real (Figure 2).2 Speaking with the building department at the City of Brampton we found their data tell the same story! The City of Brampton has made some changes in recent years to policies governing secondary suites to make the creation of legal units easier, so this trend is not that surprising.

Brampton is a good example of how much housing could be rapidly added to the Toronto CMA through the loosening of building restrictions in neighborhoods zoned residential through gentle densification or “missing middle” housing.

Meanwhile, the city of Toronto is a good example of how residential zoning protections are leading to a net decline in its existing housing stock, although some of that is also being replaced with brand new developments.

Sources:

[1] At the time of writing this blog, data was only available up to August 2021. Therefore, we estimated a final tally for the year.

[2] CMHC (2021). “Housing Market Insight, Secondary Units in Ontario.” [Online]. Available: (PDF file) https://assets.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/sites/cmhc/professional/housing-markets-data-and-research/market-reports/housing-market-insight/2021/housing-market-insight-ontario-68865-m06-en.pdf?rev=86f7979a-fdc3-4aca-90dc-8f93568b842a (external link)

Diana Petramala is Senior Economist at Toronto Metropolitan University’s Centre for Urban Research and Land Development (CUR) in Toronto.

Ryan Kyle is a Research Assistant at Toronto Metropolitan University’s Centre for Urban Research and Land Development (CUR) in Toronto.