DAS Students Win Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) Design Challenge

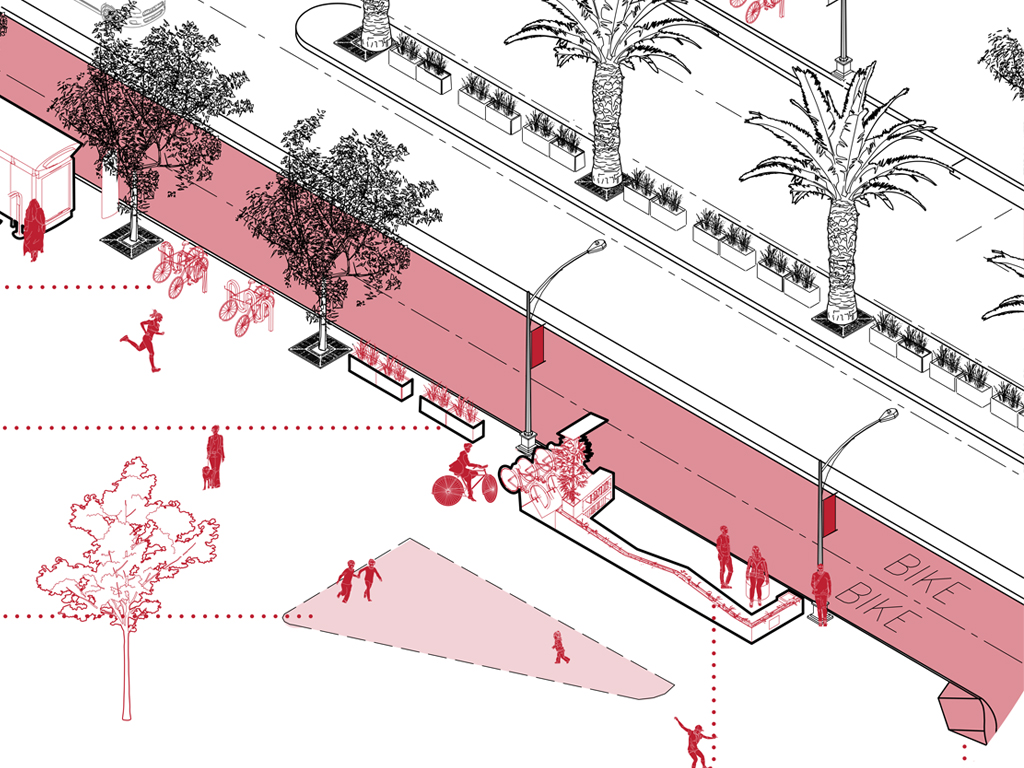

Undergraduate students Marwa Al-Saqqar and Maya Higeli, currently in co-op, collaborated with Toronto Met civil engineering students to redesign an existing traffic corridor along Bridger Avenue from Casino Center Boulevard to Las Vegas Boulevard in Las Vegas, Nevada. The team won first place in the student category at the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) Micro-mobility Sandbox Design Challenge. The design proposal realigns and widens existing bike lanes, and implements the use of a modified “Copenhagen Left” to allow micro-mobility scooters and bikes to easily navigate intersections. The design can also be implemented on Front Street West in Toronto, as well as other municipalities with existing conditions through its enhanced safety, functionality, and scalability features.

What did you find gave you the upper edge in this design challenge?

Marwa: Cross-disciplinary opportunities at DAS like Timberfever (external link, opens in new window) really provide an amazing experience that I can bring to collaborative projects. Studio and theory courses in our program also focus on the human experience and a socio-cultural approach to design, which both informs my own work and the way I collaborate with my peers. There’s the engineering side of things (such as logistics and traffic reports) and then there’s my understanding of the human approach: how does this impact the person walking down the street? How is the environment engaging to pedestrians? In the BArchSc program, I’ve really come to understand how to base a lot of design work on research and theories developed by activists and urban planners such as Jane Jacobs. This really helps us address the dominance of car culture with respect to American streets: having been taught to engage with theorists that focused on human-based design flowed really well into our design and discussion with our civil engineering teammates.

Maya: I agree, especially since this is an engineering-driven project. Our approach is very much about the human experience of the streetscape itself, rather than the data.

Marwa: The fact that we are able to bring the project together through a unifying design concept makes the project stronger: it brings the whole design back into something. We looked at precedents in Amsterdam which focus on micro-mobility, for example: how can we learn from designs and stories in other cities and apply that to American streets while also taking their context and historicity into account?

Maya: The undergrad program ensures we are technically prepared and introduces us to software tools early on - this makes our workflow smoother and allows us to collaborate with our civil engineering teammates more easily and clearly. At the end of the day, we want to ensure we can successfully communicate our proposal in both visual and technical terms.

Can you tell us about what “micro-mobility” means and why micro-mobility infrastructure is important for cities?

Maya: Micro-mobility focuses on walking, bikes, and essentially anything that isn’t a car - it reintroduces the notion of the human scale and walkability of the city, and so is an integral part of redesigning a streetscape. Our design of the King St. parklet, for example, is also based on these principles.

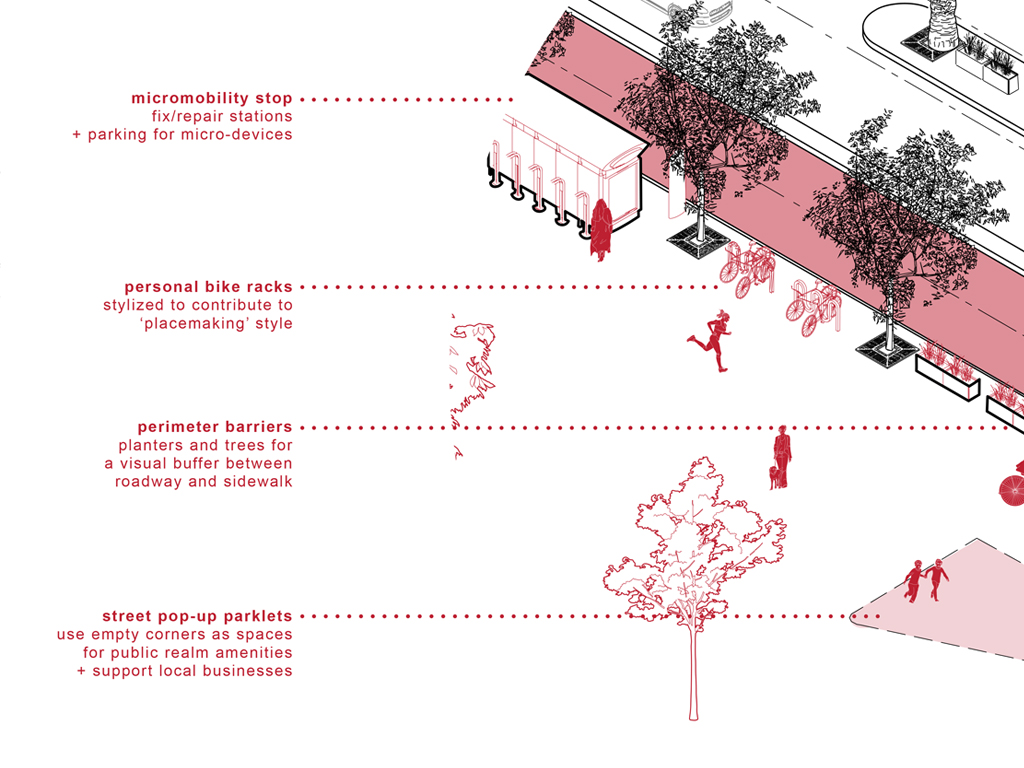

Marwa: Micro-mobility is a larger umbrella term which also involves small personal vehicles, scooters, and other low cost, low environmental impact modes of transportation--anything that allows commuters to efficiently travel through urban centres without the use of cars. Our intention is to also design something scalable and modular which can be used in different cities. We demonstrate, for example, how our proposal could work in Toronto as well (specifically on Front St. West). Inviting micro-mobility use can have a big impact: not only is it sustainable, but it also boosts the safety and wellness of pedestrians. It’s nicer to walk through a space that isn’t gridlocked by idling, noisy and polluting cars. Encouraging and advocating for streets and municipalities to engage in ways to incorporate safe and functional micro-mobility lanes affects the rest of the streetscape, and can create or support a sense of place, of community.

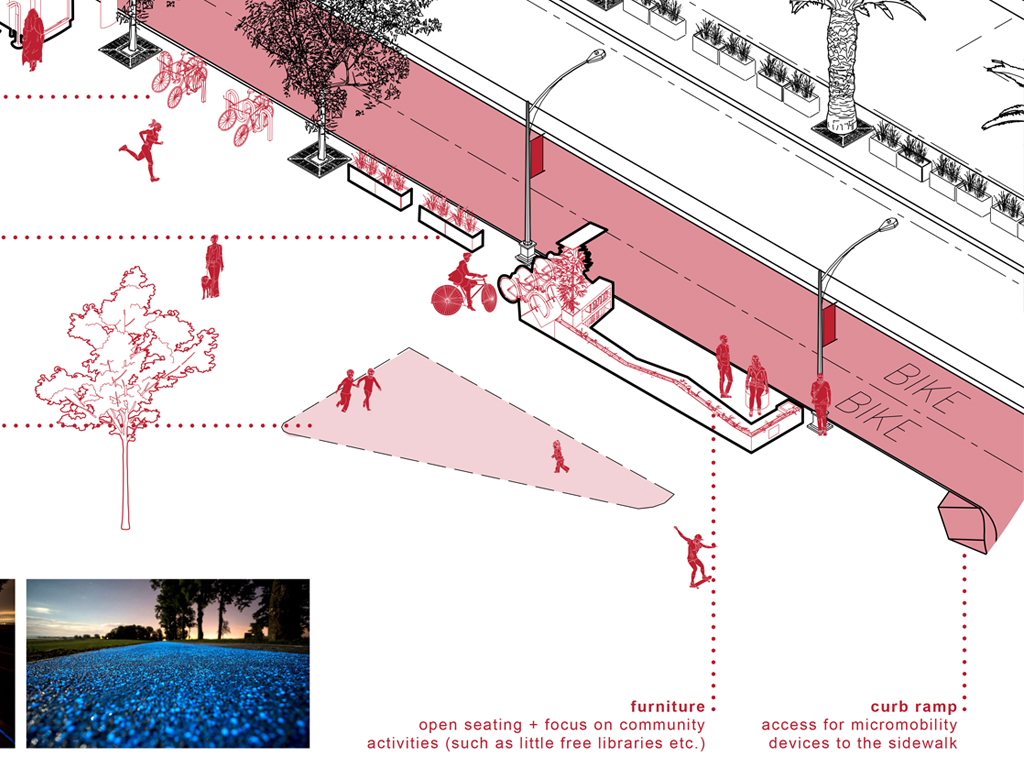

Maya: The King street parklets are an excellent example of this – less cars are allowed onto the street. I feel safer and more comfortable as a pedestrian in these spaces.

Sustainability is not just an environmental concern – it is also about social and economic aspects, and how neighbourhoods function in the space. How can we ensure that we are not limiting spaces for certain communities, and how can we help them thrive?

Marwa: Another consideration we have is how to revive main streets during pandemics. How can we get these streets to be a destination and not just a space to circulate and move on from? As a commuter looking for a place to rest during the busy day, it’s nice to walk or bike along streets revived through visual and other senses which indicate safety within the space. Cities need to take the time to design their lanes, and not just take out 0.5 meters from a car lane and call it a bike lane. This is why it’s necessary for civil engineers to take the time to focus on the traffic aspect of the lane, the logistics of traffic lights - and why architects can consider things like events and pop up spaces (for example) that community members and artists can use, without running into circulation or safety issues.

Can you speak to how the project ties to sustainability?

Maya: Micro-mobility is about more sustainable ways of traveling throughout the city. This can mean more bike lanes and bigger sidewalks, as well as encouraging the use of parklets.

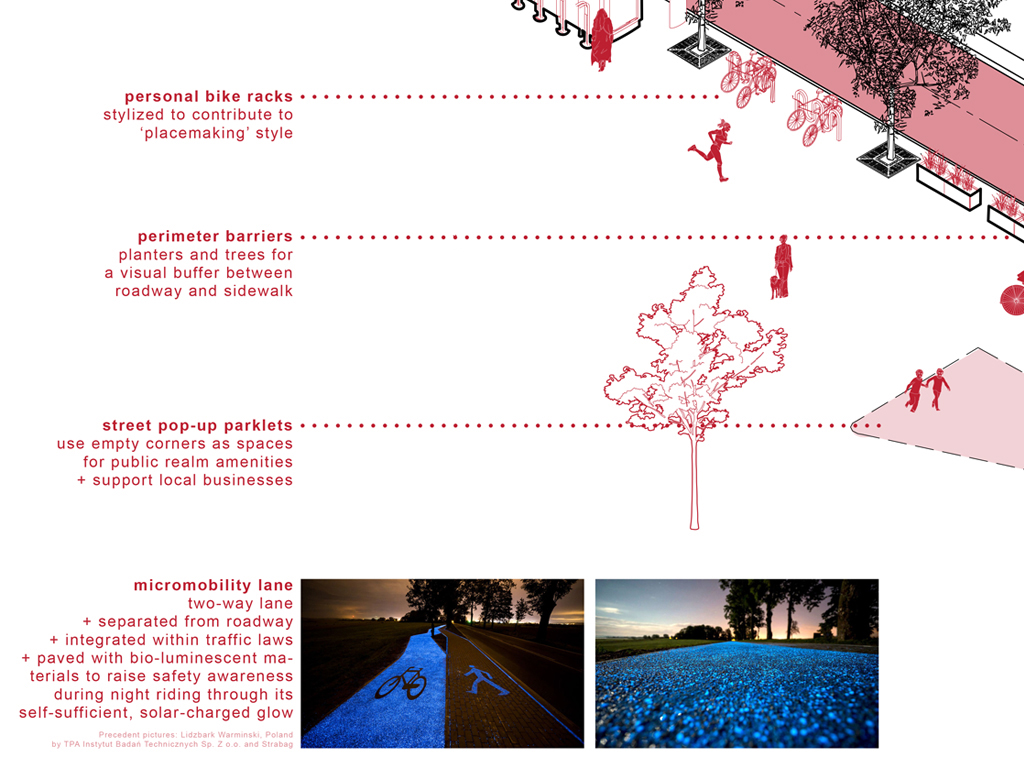

Marwa: We also considered different materials that use sunlight or solar energy to light up (bioluminescent materials). We haven’t proposed it in this project – but in general, the challenge itself allowed us to look into more innovation in materiality and constructability aspects that are low cost and low environmental impact. Whether it’s the curbs or the water system, permeable materials within the sidewalk allowing for water drainage are important. I would like to also add that sustainability is not just an environmental concern – it is also about social and economic aspects, and how neighbourhoods function in the space. How can we ensure that we are not limiting spaces for certain communities, and how can we help them thrive? Economic prosperity, mental wellness, as well as environmental sustainability for the people and living things within the space is a very larger driver for us. Micro-mobility ties in well because it’s something that can impact the rest of the street in these economic, social, and environmental ways.

Maya: The mental health of people engaging in the streetscape is very important. We also look at plastic road module panels to allow rainwater storage, for example.

What is the strategy/thinking behind the two-part solution you have developed in terms of road design and landscaping, broadly speaking?

Maya: Accessibility is a big concern, from using bioluminescent materials to how the curbs dip down at pedestrian crossings.

Marwa: The design can be implemented in other cities, so there is a certain element of flexibility built into the road design and landscape: whether it’s native vegetation, or local artists engaging with the space. Community engagement is important to us: it allows an identity to flourish from that street. What we understand to be an “all American” street (both historically and culturally) should be defined at the community level, and the community should be involved - whether it’s through the decision-making around the design, or how the space is actually created.

What was it like to build a connection with your peers in civil engineering?

Maya: Going in, we didn’t know anything about road construction. In the end, it was a great learning experience for both of us, and working out the differences in terms of how we think – sometimes engineers approach things using data (how to solve a problem logically). We learned a lot.

Marwa: The final proposal is reflective of a joint effort, of learning from each other. Not only has our experience in co-op given us a more “down to earth” approach to our design, but we now have our workflows and are learning to find opportunities where we can pitch in and help one another. Working with ShapeLab and the King Street parklets also gave us real-world experience on how to work towards a common goal.

Maya: It’s important to learn that there are so many diverse perspectives and ideas, such as the data-driven approach, for example. Real-world experience means there will be different ways people approach the same problem: knowing how to work together makes me a better designer.