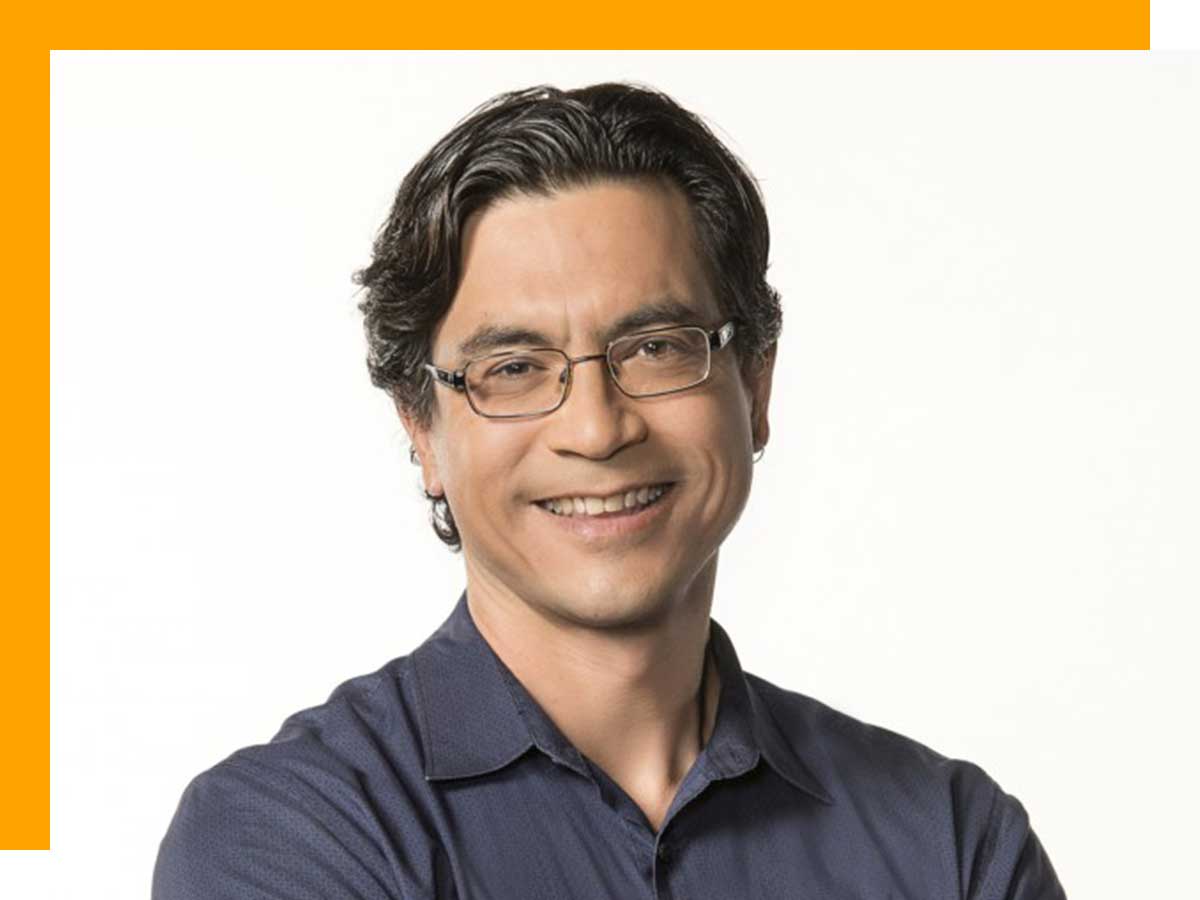

In conversation with Duncan McCue: veteran reporter and Rogers Journalist in Residence, School of Journalism

Last year, the federal government announced September 30 would be formally designated National Day for Truth and Reconciliation (external link, opens in new window) . This statutory holiday provides an opportunity for Canadians to reflect on the dark legacy of Residential Schools in our country and honour the lost children, Survivors, and families of the Indigenous communities impacted by this system.

In recognition of this day, we chatted with veteran reporter and Rogers Journalist in Residence at the School of Journalism, Duncan McCue. With over two decades of experience, McCue is an award-winning journalist and host of the CBC podcast Kuper Island (external link, opens in new window) — an eight-part series on residential schools in Canada. His work has garnered several RTNDA and Jack Webster Awards. In addition, he was part of a CBC Aboriginal investigation into missing and murdered Indigenous women that won numerous honours, including the Hillman Award for Investigative Journalism. In 2017, he received an Indspire Award for Public Service. McCue teaches journalism at Toronto Metropolitan University and the UBC Graduate School of Journalism and was recognized by the Canadian Ethnic Media Association with an Innovation Award for developing a curriculum on Indigenous issues.

McCue is Anishinaabe, a member of the Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation in southern Ontario and the proud father of two children.

What inspires your passion for sharing Indigenous stories and educating Canadians through your work?

I got into the business over 20 years ago because I saw a lack of representation of Indigenous voices in the news, which troubled me. As an Indigenous person, I felt it was important that Canadians had an opportunity to hear our stories and not just the stereotypical news events that seemed to pop up from time to time, such as blockades over land rights or tragedies. I knew that Indigenous people are consumers of news in this country and that there's far more. This does not mean blockades and tragedies are not newsworthy, but merely that there is far more news in our communities than we saw presented two decades ago. I wanted to help broaden the range of Indigenous voices we saw on our nightly TV and radio newscasts.

In 2011, you created an online guide, Reporting in Indigenous Communities (external link, opens in new window) , for journalists in Canada. Why was this tool essential, and what impact has it had on the Canadian journalism landscape?

The representation of Indigenous news was an important goal of mine. One of the things that we observed at CBC was that non-Indigenous journalists were facing challenges when pitching Indigenous news stories and going into Indigenous communities to cover them. Over a decade ago, there was no resource for them. My goal behind this idea to create the online guide and make it a free, open resource was to start a conversation about recognizing some of the problems in the coverage. I wanted to offer tangible, practical ways journalists can change their practices to better interact with Indigenous communities. It was designed for working journalists, so it was written in a way that would be accessible, practical, and conversational for journalists who are on a tight deadline. As it turned out, the largest consumers of the guide were journalism students and professors. It's been so well received that I've updated it to include more material, and Oxford University Press will publish it in October. The new textbook will be called Decolonizing Journalism: A Guide to Reporting in Indigenous Communities. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has said part of reconciliation is teaching Indigenous history and culture in journalism classrooms, so I hope the textbook helps fulfill that goal.

What motivated you to become an educator?

I have been very fortunate to work at CBC my entire journalism career. I received outstanding training throughout the beginning of my career, and I wanted to share that with students. I believe that if we're going to have better coverage of Indigenous communities in the news, we need to include non-Indigenous journalists and bring in more young Indigenous journalists. The best place to reach the next generation is in journalism school. It’s imperative young journalists have the opportunity to learn about diversity — in my case, it's teaching them about Indigenous communities. These students need to have a safe space to learn how to do this, which isn't in a newsroom with deadlines, where the results of their work are public-facing and can unintentionally cause harm. This is why I started teaching, to create a space for discussion about diversity in our coverage.

You're the host of the CBC podcast Kuper Island. Why is it important for stories like these to be brought to light? What do you hope Canadians will take away from this series?

CBC podcasts approached me about hosting the podcast last summer after the news of unmarked graves became public. There are a few reasons why I decided to host the podcast. First, I recognized the critical role of journalism in sharing that buried part of Canada's history. So many Canadians are trying to learn more about residential schools and particularly, the deaths of children in residential schools. Although podcasts are relatively new and have exploded during the pandemic, there wasn't much content on the subject of residential schools in the podcast space. Secondly, I hoped to go beyond the numbers. Last summer, it seemed as though school community after community was announcing there were unmarked graves at former residential school properties. The numbers kept climbing higher, so what I hoped to do with the podcast was help Canadians understand that deaths at the schools are not a thing of the past. These deaths reverberate to the present day, and it's more than just cold, hard numbers. These are real children who died at the schools, and it impacted their families for generations. So, I hope this podcast will help put a human face to the tragedy of generations of children dying at residential schools.

What impact do you hope the formal recognition of National Day for Truth and Reconciliation in Canada will have? How do you hope this will move the conversation about reconciliation forward?

It is incredibly important that this day was recognized as a statutory holiday. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission made this one of their calls to action because they wanted it to be an ongoing conversation and education about the history of our country. Canadians need to understand that the residential schools lasted for several generations, and their impact will reverberate for several generations.

I hope this day is observed in much the same way as Remembrance Day. Yes, it's about remembering the soldiers who died in historical wars, but it's also much more. It's a broader acknowledgement of the atrocity and the horrible nature of war itself. I hope National Day for Truth and Reconciliation becomes a recognition of the relationship with Indigenous people in Canada that went horribly sideways for one party in what was supposed to be a trust in a sacred relationship. I hope that repairing the relationship is an ongoing, reciprocal obligation on both sides. This day should not only mean looking at black and white archival photos and feeling guilty. It means looking at young Indigenous youth today and seeing if they have the opportunities, resources and pride their ancestors imagined they would have in their homelands. The question I hope Canadians will ask themselves every September 30 is, “are we doing our best to make sure that First Nations, Métis and Inuit youth have strong nations that are important parts of the Canadian economy and cultural sector?”